“That’s still a cemetery and there’s going to be some form of reckoning with this history.”

With those words in September 2004, local historian Jim Wolf presented the New Westminster school district with a puzzle it has been working on for more than a decade – where to build a giant new high school without disturbing what could be thousands of human remains beneath.

At first, though, the school board was unruffled by Wolf’s foreboding statement.

“I’m sure the people who constructed the school followed all the guidelines that were in place at the time…I’m not prepared to spend any education dollars on studying this in-depth at this point,” said then board chair Brent Atkinson in 2004.

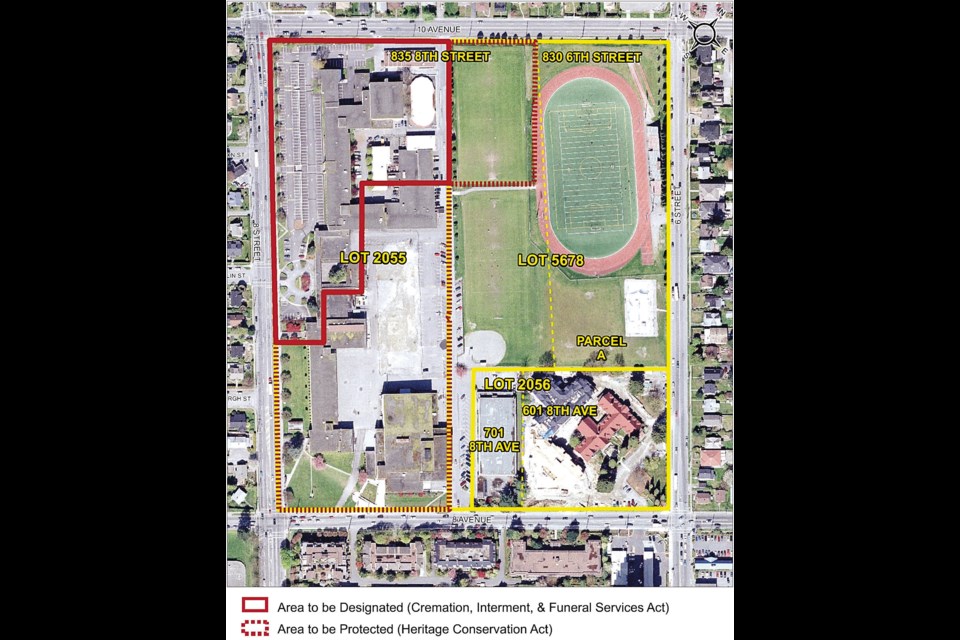

After numerous studies, some including electromagnetic and ground-penetrating radar imaging, however, the latest estimates show more than five acres of the site cannot be built upon because of a cemetery, the Douglas Road Cemetery, that was never properly decommissioned before the city sold the property to the school district in the late 1940s.

In recent years, the city has taken back some of that property in land swaps with plans to convert it into passive park space, leaving the district with enough space for a new high school.

But even the land the district plans to stick its shovels into next summer might turn up bones, so an archeologist will be on site during all excavations, according to director of operations Doug Templeton. The district’s project development report also proposes a reserve fund of $7,000 per set of remains to have them properly handled.

“That’s what we’ve been told it would cost to deal with it,” Templeton said.

The cemetery operated from around 1860 to 1920 and was first used as a pioneer graveyard.

Eventually it became a potter’s field – the final resting place for the poor, prisoners, stillborn babies and mentally ill patients.

It was also a burial ground for Chinese and other non-European groups, including Sikhs and First Nations.

At least one individual buried there made a reappearance in 1949, when builders unearthed a coffin during construction of Massey Junior High School.

In 2008 it came to light that Tsilhqot’in Chief Ahan might have been buried there after being executed in 1865 in New West for his part in the Chilcotin War.

At one point the Tsilhqot’in First Nation threatened to seek a court injunction to stop the high school project until his remains were found, but a subsequent study showed the chief was likely buried by the site of the old courthouse downtown.

The cemetery takes up roughly the Pearson wing of the high school, which runs from about 10th Avenue and Eighth Street to Dublin Street.

The Massey wing is considered “low-risk” for human remains because it housed what was called the “old Chinese cemetery,” and Chinese cultural practice involved removal of remains after a number of years of re- interment.

The Business Practices and Consumer Protection Authority - the government body that oversees cemeteries - has designated a portion of the NWSS site a cemetery, and the rest now falls under the Heritage Conservation Act, which will allow the district to proceed with construction under certain conditions.