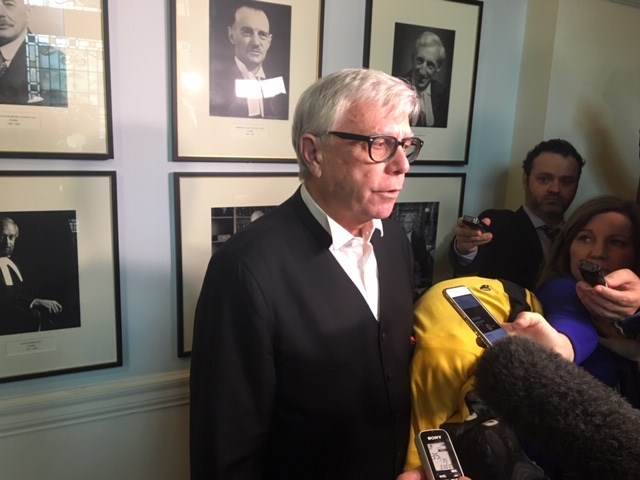

Craig James, the B.C. legislature’s former clerk, acted with intent and ignored an obvious conflict of interest when he directed accountants to pay him over a quarter of a million dollars for a retirement benefit he knew he wasn’t entitled to.

That is part of Crown prosecutor Brock Martland’s closing argument in a criminal court case against James, who is charged with two counts of fraud and three counts of breach of trust.

James became clerk in September 2011 and within months was directing a lawyer to form a legal opinion that he would eventually use to obtain a $257,988 retroactive retirement benefit for himself. Martland said James was never eligible for the benefit as it was cancelled in 1987, the year he was hired as an assistant clerk.

The benefit is central to the breach of trust allegation, whereas James’ alleged improper personal expenses and use of legislature property forms the fraud charges.

The evidence tendered by special prosecutors Martland and David Butcher largely relies on the fact the legislature lacked clear policies on conflict of interest and personal expenses during James’ time as clerk, between 2011 and 2018. James was terminated in 2018 following an independent investigation by then-Speaker of the House Darryl Plecas.

Associate Chief Justice Heather Holmes has heard testimony from a number of past and present legislature employees, many of whom are accountants tasked to oversee the financial management of the Parliament Buildings.

The court has heard a lengthy explanation over how the benefit came to be and how James was eventually issued it.

Holmes has seen documents showing the benefit was issued in 1984 to several part-time clerks, in lieu of a standard pension. It was capped in 1987; moving forward, all clerks would be issued a standard government pension and a 10% pay raise, as James received.

Fast forward to 2011, following his appointment by the BC Liberal government, James, the legislature’s de facto CEO, was confronted with the threat of a lawsuit against the legislature by retiring assistant clerk Robert Vaive, who was dying of cancer and said he was entitled to the benefit.

Vaive submitted he was entitled to the retroactive payments. At the same time, law clerk Ian Izard was to be paid; however, documents shown to court indicate Izard had not opted out of the benefit in 1987 (didn’t take the pay raise and standard pension) and so there was little controversy about his payout.

So, James sought a legal opinion on Vaive from lawyer Donald Farquhar, who provided one orally to Speaker of the House Bill Barisoff, who eventually had to sign off on the payout. Farquhar was of the opinion Vaive had a case and there was some apparent sympathy toward him from Barisoff, the court heard.

Holmes questioned Martland many times on the evidence, including on the wording of the documents showing the benefit being capped. Farquhar testified that it was his opinion the capping was only specific to people named in the old documents (which did not include James).

Farquhar also testified he only provided an oral opinion to Barisoff and only for Vaive.

But come February 2012, when payroll manager Dan Arbic inquired by email about who would be paid out the benefit, it was James who responded to Arbic, indicating he himself would be included in the final payouts as well — this despite Barisoff not explicitly instructing Arbic to pay James.

“Mr. James is shown to be thinking about his own retirement benefit eligibility,” said Martland.

“That he directed his own payout was an intentional conflict of interest and abuse of his power,” Martland argued.

“He had a clear duty to abstain himself from any duties in the process,” said Martland.

“Rather than stepping back from an obvious conflict of interest situation …Mr. James is actively involved and in fact impatient to have his payment made,” added Martland.

Unlike Izard, who received notice from legislature accountants he was eligible, no such documentation existed for James, according to the prosecutors.

In essence, argued Martland, James concocted his own payout.

“He was not entitled to the benefit; he was never entitled to the benefit. He was not on the same footing as those other officers,” Martland told Holmes.

Key to the prosecutors’ case is to show intent by James.

To do so they point to how James initially showed concern that Vaive’s payout was questionable. They allege James was opportunistic in the face of unclear rules and policies.

“Those concerns evaporated. He saw an opportunity for himself and he took it. He used his position to enrich himself,” said Martland. “He manoeuvred to engineer a quarter-million-dollar windfall, or so-called retirement benefit,” said Martland.

And, Farquhar, the lawyer, did not conduct a thorough review of the policy, argued Martland. Instead, he relied on James providing information on it.

James “was the one providing instruction to counsel, information to counsel and documents to counsel that would be used as the basis for a legal opinion.”

Court heard from Farquhar that he became a retained lawyer after December 2011, for about $4,000 per month.

Barisoff testified he depended on the trust of James and other senior officers at the legislature.

“We say Mr. Barisoff’s trust in Mr. James was naive and is proved to be misplaced,” Martland told the court.

Closing arguments on the fraud charges related to expenses are expected Wednesday.

Defence lawyers Gavin Cameron and Kevin Westell did not put forth a case (leaving it to prosecutors to form their case) but are expected to offer closing comments as well.