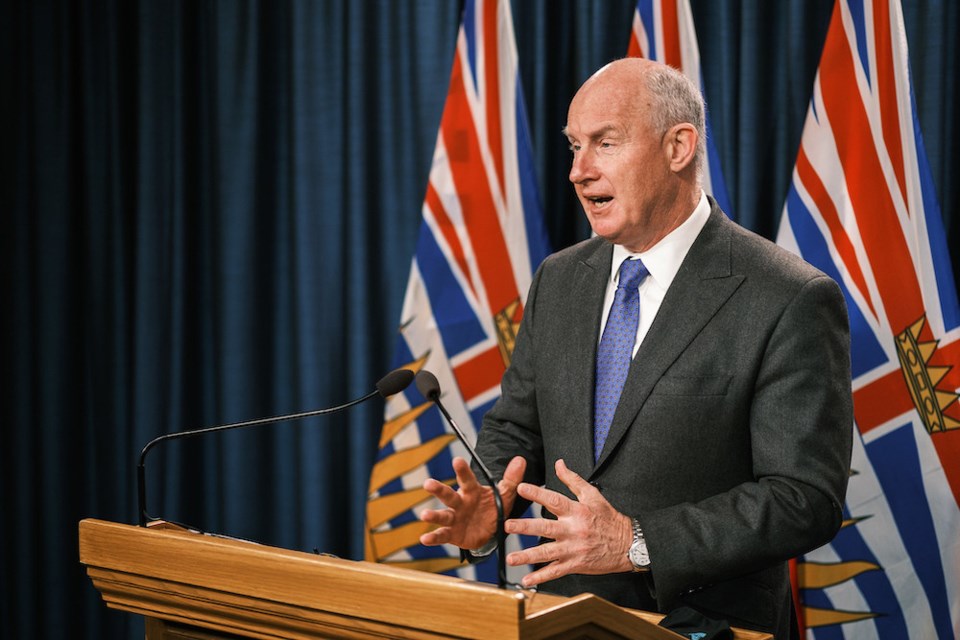

The province moved immediately to increase the security on its computer networks before informing the public of a cybersecurity incident to ensure the system wasn’t compromised further, Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth said Thursday.

Farnworth was responding to questions in the legislature about why the government waited at least eight days to announce it had identified “sophisticated cybersecurity incidents” involving its computer networks.

Premier David Eby said in a statement sent out just before 6 p.m. Wednesday that the provincial government was working with the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security and other agencies to determine the extent of the incidents, but there was no immediate evidence that sensitive information had been compromised.

Farnworth said that protection of the system is the first priority “when an incident like this happens,” adding that technical experts are working on the advice of the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, a federal agency.

“The moment our technical security experts become aware of something their first priority is to protect the system, to understand what’s taken place, and the challenge with going out right away and telling people that, is the moment you do that, if you haven’t secured everything, if you haven’t understood what’s taking place you are then making the system more vulnerable to outside interference.”

A thorough investigation involving several agencies including police is ongoing and the priority is to ensure the system is protected and that information is protected, he said.

Provincial government computer systems hold a wide array of sensitive information from social insurance numbers and financial statements to health and social services records.

Threat analyst Brett Callow, based in Shawnigan Lake, said most cyberattacks involve ransomware, where an intruder gains access to a network, blocks or encrypts the system, and then holds the victim’s data or device hostage, threatening to keep it locked or release information publicly online if the victim doesn’t pay up.

“Most often it’s done for money,” said Callow, “but there can be other motivations from espionage to activism.”

Ransomware software is most often created in Eastern Europe, particularly Russia, although the affiliates who use the software and carry out the attacks “can be based absolutely anywhere,” said Callow, who works for Emsisoft, an anti-malware and anti-virus software firm.

Farnworth, however, in a media scrum, said that “the one thing I can confirm is that this has not been a ransomware incident.”

Callow, who is not involved in the B.C. government’s investigation, said he would take the claim that the hack was “sophisticated” with a grain of salt. “Most of these attacks aren’t particularly sophisticated,” said Callow. “They are formulaic and often succeed due to some pretty basic security failing.”

Some of the more common failings include not using phishing-resistant, multi-factor log-in systems or not having applied a security patch to a system that has a known vulnerability, he said.

Farnworth reitereated Thursday the premier’s statement a day earlier that “there is no evidence at this time that sensitive information has been compromised.” Farnworth said the government was told that had it not been for upgrades it made to the system in 2022 the breach may not have even been detected.

“Working out whether or not information was compromised, requires a forensic investigation that can take weeks or even months,” Callow said.

Even if the intruders are identified, apprehending them is a long and complex process complicated by the fact the criminals may live in countries where no extradition agreements exist, Callow said. “This is happening to massive companies, it’s happening to governments, and unfortunately it’s not at all uncommon.”

Eby said the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner was informed and that the government would be as transparent as it could “without compromising the investigation.”

In a media availability on Thursday, BC United Leader Kevin Falcon said the government has been anything but transparent.

“We know that for at least eight days they’ve known that this was an issue and last night they quietly released a statement in the midst of a Canucks playoff hockey game,” said Falcon, contrasting the response with London Drugs’ reaction after it was the target of a cyber security breach.

The retailer shut its stores in Western Canada for more than a week and its CEO made it clear to customers the incident had taken place, he said.

Government staff received an email Wednesday from Shannon Salter, deputy minister to the premier and head of the public service, informing them of the cybersecurity incidents and directing them to change their passwords from 10 characters to 14 in an effort to “safeguard our data and information systems.”

Salter, in the email obtained by the Times Colonist, said as more information becomes available she will share what she can “without compromising the ongoing, complex investigation.”

On April 29, all B.C. Emergency Health Services workers received a similar message from managers, informing them of a “mandatory password change.”

The email includes suggestions on how to make passwords more robust.

Asked late last week whether the directive was related to a cyberattack, Eby said the Office of the Chief Information Officer of B.C. directed public service employees to change their passwords to ensure the security of government email systems, as well as information systems.

“That’s all I can share at this stage, but they’re doing some work on this issue and I expect to have more to say soon.”