The names in his family tree read like a North Vancouver road atlas – Heywood, Lonsdale, Pemberton, Fell. It was once a source of pride.

But recent study into Guy Heywood’s family history reveals a dark and forgotten truth. The early settlement of the North Shore, its continued development, and the formation of the City of North Vancouver as we know it today all flow from a family fortune amassed in the transatlantic slave trade.

“It’s sobering,” said Heywood. “Racism is pretty deep in our [Canadian] history as well, but this was a surprising connection.”

How profits from the slave trade came to North Vancouver

Researching the family tree became a retirement project for Heywood’s father Bob, who was a detachment commander of the North Vancouver RCMP and, later, a city councillor. They already knew about the more recent generations of the family and the role they had in the early settling of North Vancouver.

To make the familial and financial lineage clear, it helps to work backward.

The City of North Vancouver was carved out of the larger District of North Vancouver in 1907, with its borders drawn largely around the land holdings of Lonsdale Estates and the North Vancouver Land Improvement Co.

Lonsdale Estates was co-owned by James Pemberton-Fell and Henry Heywood-Lonsdale (1864-1930). He was the son of Arthur Pemberton Heywood-Lonsdale (1835-1897) who led the syndicate of investors that financed the Moodyville Sawmill, the first industrial development on the North Shore with a settler community built around it. When the sawmill went bankrupt, Henry Heywood-Lonsdale consolidated the debt and land into Lonsdale Estates, with plans to develop the land.

Arthur Pemberton Heywood-Lonsdale inherited his ₤1.25-million fortune from his uncle John Pemberton Heywood the younger (1803-1877), who worked in the family-owned bank in Manchester. His father was John Pemberton Heywood the elder (1756 -1835), son of Arthur Heywood and nephew of Benjamin Heywood, who had established the bank in 1790.

The Heywood family lived on estates around Liverpool and Manchester, some of which would have familiar names – Calverhall, Shavington and Cloverley.

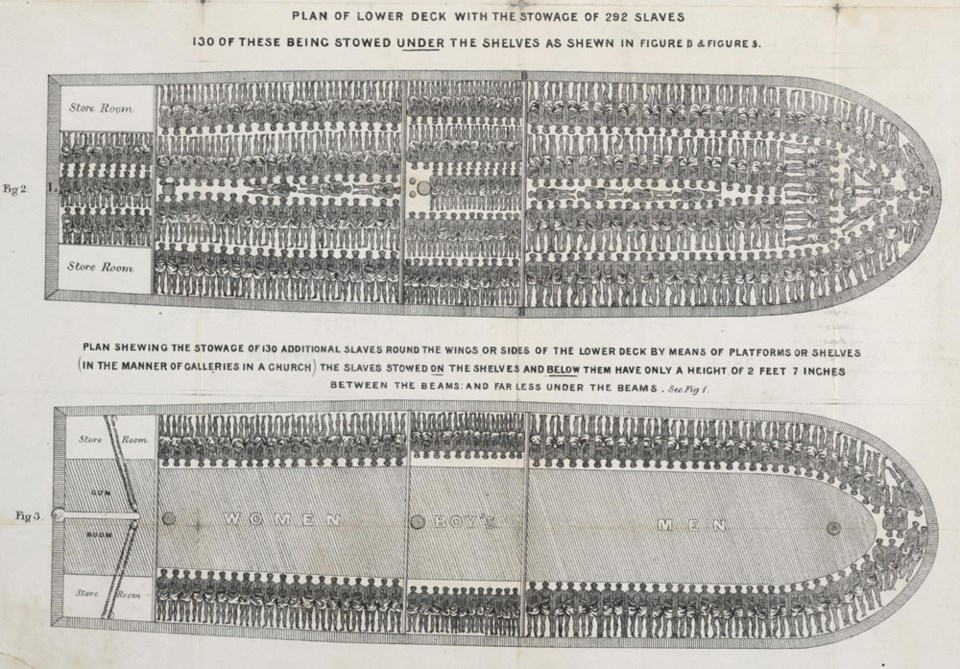

Before they got into banking, Arthur and Benjamin Heywood owned at least two ships used in the slave trade, a historic fact already documented by British academics. The Heywood brothers’ ships, Phoebe and Prince of Wales, sailed between West Africa and the West Indies. Phoebe carried 280 slaves from the Gold Coast in 1753, records show, and the Heywood brothers invested in 133 voyages up until the late 1780s.

Generations passed and the money was “washed” through banks, Heywood said, but the moral culpability behind the capital remains.

“I'm trying to do whatever I can to get people to question the way things are, and ask whether they always need to stay that way,” he said.

The human cost of the Heywood family fortune should never be lost amid numbers and dates, said June Francis, associate professor of marketing and business at Simon Fraser University and chair of the Hogan's Alley Society in Vancouver.

“This number represents absolute untold, indescribable inhumanity – to think of a person becoming chattel and what that gives them rights to. ... The fact that people survived this is really the biggest mystery to me,” she said. “They made the calculus that it was cheaper to get new slaves than to reproduce slaves, so then they'd work slaves to death.”

Shining a light

Guy Heywood descends from Benjamin and Arthur’s brother Nathanial (1726-1808), who was a soldier and does not appear to have been involved in the family business. Heywood’s grandfather arrived from England in the 1920s and settled in Abbotsford to farm chickens.

It was around 2016 when Heywood came to understand the connection between North Vancouver and slavery, though he was never quite sure what to do with the information.

Then, Heywood said a series of events raised his consciousness and he felt compelled to speak up.

A 2019 New York Times series about slavery’s history and legacy got Heywood thinking about the broader implications.

“The thesis is that really, the American economy got its bootstraps from slavery,” he said. “That kind of realization talks about just how deeply rooted racism is in not just culture, but it’s in the foundations of the economy.”

The 2020 murder of George Floyd spurred a wider reckoning with anti-Black racism.

Heywood said he couldn’t help but feel the contrast with the contributions his partner Christene Best’s family has made to Black history in Canada. Her ancestors joined the first Black settlement on the East Coast in 1787.

Her grandmother Carrie Best was arrested in 1943 for sitting in the white section of a segregated Nova Scotia theatre. Later, she established the New Glasgow Clarion, the first black-owned newspaper in the province. When Viola Desmond was arrested for doing the same thing in 1946, the Clarion broke the story and challenged racial segregation at the theatre. Carrie Best was later named to the Order of Canada. Desmond’s face is on the $10 bill.

In 1967, Best’s grandfather, Isaac Phills, was the first Black man invested to the Order of Canada. He was a First World War veteran who put his seven kids through university, despite tremendous adversity.

And Best’s father, James Calbert Best, founded and led the Civil Service Association, became the highest-ranking Black person in the federal civil service, and was the first Black Canadian to represent the country as High Commissioner at Canada’s mission in Trinidad and Tobago.

Not just North Vancouver

Francis said the revelation that an institution of modern-day Canada is the legacy of slavery did not come as a surprise to her because there are so many others.

“Collateral in slaves provided much of the initial financial beginnings of the mortgage industry,” she said. “That was the asset base of much of the North American economy.”

Other industries arose in the service of slavery. While Liverpool became a centre for shipbuilding, finance and insurance because of its status as a hub for the slave trade, much of the cod that was harvested from Newfoundland in the earliest days of its fishery was used to feed slaves, Francis said.

When Empire Loyalists arrived in Canada during the American Revolution, many brought their slaves and their fortunes with them. Slavery was only abolished in the British Empire, including the colonies of what is today Canada, in 1834.

The wealth amassed through slavery, both direct and indirect, and still circulating in the economy, is estimated by academics to be in the trillions of dollars, Francis said.

And startlingly little of it has been shared with the people on whose backs it was created.

The Heywood family bank was later absorbed into other banks, which were themselves absorbed into Barclays Bank in the 1960s. Today, Barclays is the subject of lawsuits seeking reparations for slavery.

“The argument that many people are trying to make for reparations is to say it wasn't just a human disaster, but an economic disaster. It used the institution [of slavery] itself to generate wealth. That wealth begat wealth, which then helps perpetuate the exclusion,” Francis said.

There’s a reason slavery’s shaping of modern-day Canada is overlooked, Francis said. No small part of it is the Canadian habit of dismissing both slavery and racism as America’s problems, not our own.

“We have so under-invested in research around the issue of slavery in Canada,” she said, noting funding is usually directed to areas other than Black history. “Our history has largely been ignored and erased and not properly documented and not retained.”

The injustice that persists is that once established, North Vancouver continued as a place that excluded Black people, even though it would not exist as we know it today without their enslavement.

There are developments across the North Shore that came with legal covenants specifically forbidding people of Asian, African or Indian descent from owning property here.

When the late track star Harry Jerome’s family moved to North Vancouver in 1951, there was a protest held by neighbours to keep them out. The Jerome children were pelted with rocks and racial slurs on their way to school.

According to the 2016 census, less than one per cent of City of North Vancouver residents identified as Black.

“I used to live in North Van and I chose to leave because I did not feel it was a place I could reasonably raise a Black family or a mixed-race family,” Francis said.

Name and place

With North Vancouver’s forgotten roots in the slave trade becoming exposed comes the question of what to do about it.

Heywood expects there will be discussions about whether the family name should disappear from local parks and street signs. He doesn’t object and he believes there are some names of other property speculators that should be replaced with ones more connected to the community. But, more than that, Heywood said it puts the legitimacy of the City of North Vancouver itself into question.

“If we're going to question names, maybe we should question borders,” he said. “History is not benign. And the things we have done need not be respected just because they were done a long time ago.”

Undoing his distant cousins’ creation, admittedly, is something he favoured before learning the full family history. Carving the city out of the District of North Vancouver in 1907 has done nothing but warp the community’s sense of itself and create a confounding mess of jurisdictions and policy, he argues. But Heywood said the revelation comes at a critical time when people have never been more reliant on government, yet faith in government has been eroding.

“We can't really afford to let things that gnaw away at the legitimacy of governance go unaddressed,” he said.

For Francis, acknowledging the history is a welcome first step.

“If we exclude the contributions, either directly or indirectly, of Black Canadians, then Black Canadians themselves don't get to enjoy the pride of place,” she said.

But simply swapping out street and park signs would be a maddening mistake if it does not also come with more substantive efforts to restore what has been taken away. The Hogan’s Alley Society came about because the City of Vancouver made plans to provide a new plaque commemorating the black community of Vancouver that was evicted to make way for highway infrastructure, but the city offered nothing else to address the lasting impacts of racism.

“Once we understand that we have benefited from this investment and that certain people are living off the affluence of that historic stain and wrong, then comes the question of how do we redress that?” she said.

Addressing systemic racism – that which produces inequalities in education, justice, housing, employment, health care and cultural representation, ought to be the focus going forward, Francis said. It’s a process that should be centred around the contemporary lived experience of Black people, whether they are current residents or not, who know best how to identify where they are excluded still.

“There's a lot of ways in which this thing continues to ripple through the society that creates a sense of isolation and not feeling fully Canadian,” she said.

Best said her experience as a Black woman in North Vancouver has not been any different from the other Canadian cities she’s lived in. But she fully agrees with Francis. Tearing down monuments isn’t particularly helpful, she said, if people believe it gives them a pass on dealing with the broader problem.

“There are wider issues of systemic racism that need to continually be addressed. And it shouldn't take an incident like George Floyd for people to really try and examine how they've shaped society and the need to make it more egalitarian,” she said. “Because, at the end of the day, we all lose when people don't have a chance to live and contribute to their full potential. And that's what systemic racism does. It prevents people from being able to do that.”