This is part one of a two-part story featuring Waffle House founder Susan Chew, whose life in New Westminster in the 1940s and '50s recall a bustling little city where a young entrepreneur could really make an impression. They also recall a nearly forgotten racist blot on that city’s history.

The party

This is not the Waffle House Susan Chew left behind when she moved from New Westminster to Toronto more than 50 years ago.

The restaurant has moved two times and passed out of the family altogether since she first opened it as a small cafe in 1955 on the corner of Sixth and Sixth.

Today, though, on Jan. 29, its newest iteration at 636 Sixth St. is packed with familiar faces.

Chew’s youngest sister, Grace Yip, has surprised her with a party for her 90th birthday and booked the whole restaurant for the occasion.

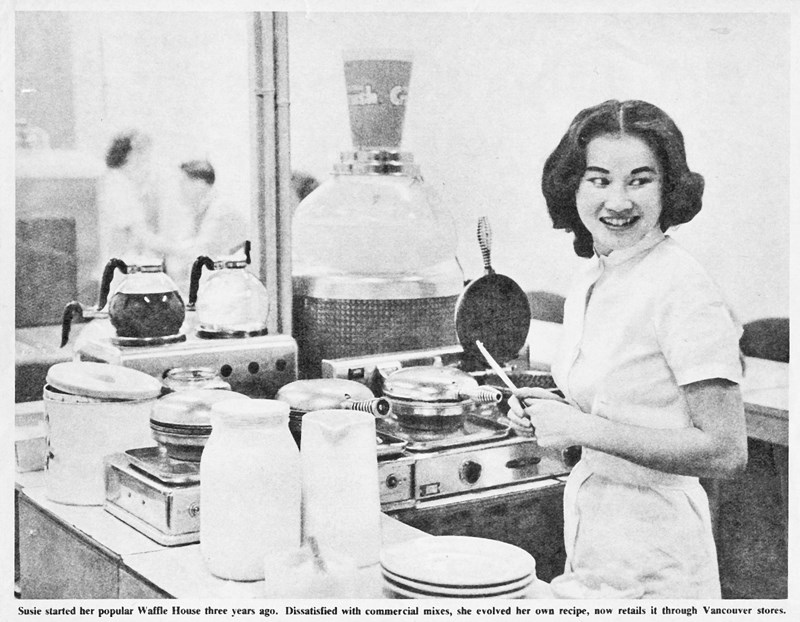

As Chew makes her entrance, someone places a wreath of orchids on her head (a nod to her years as a professional hula dancer); Mayor Jonathan Cote is on hand with flowers, and current Waffle House proprietor Robert Babayan poses with Chew in front of a big black-and-white photo of a much younger Chew working the Waffle House irons in the 1950s.

To one person in the crowd, that version of Chew 60 years ago would have been a familiar sight back in the day.

Verla Thompson (née Staples) was a waitress at the Waffle House then and Chew’s roommate in 1956.

It would be a hard year to forget.

In the course of trying to find an apartment, the pair had sparked a national news story of racial discrimination that would show the Royal City at its worst – and best.

The Waffle House

Born in Victoria, the eighth of 11 kids, Chew grew up working with her siblings on her immigrant parents’ Saanich farm.

“We worked like men,” Chew tells me during a visit to her Vancouver apartment a few days after her surprise party.

When an appendectomy made her unfit for the work, she moved to New Westminster at age 20 to help in her sister Alice’s grocery store, the Handy Fruit Mart, on the corner of Sixth and Sixth.

She took over the place in 1946 and was eyeing new opportunities when a space opened up next door in 1955.

“I decided to start a little restaurant,” she says, “and I called it the Waffle House, and I specialized in waffles.”

Was it normal in the late 1940s – before the women’s rights movement of the 1960s or the repeal of Canada’s infamous Chinese Exclusion Act – for a young, single, Chinese-Canadian woman to launch her own independent business ventures?

“No, that was just Susie,” her sister had told me with a laugh earlier. “She did all these kind of things that regular people didn’t have the initiative to do.”

“I guess I was born with a lot of confidence in myself,” Chew says.

If there were people in New Westminster in the 1940s and ’50s who thought being Chinese-Canadian should have limited her role in the community, their feelings hadn’t yet registered with Chew.

Even before opening the Waffle House, Chew had organized fundraising efforts for victims of the catastrophic 1948 Fraser River flood; she was a Cubmaster at Holy Trinity church, belonged to skating and tennis clubs, modelled in fashion shows and studied music.

The Waffle House, meanwhile, became a popular hangout for both young people and reporters in the 1950s, when the Columbian newspaper published daily in New West and CKNW still broadcast from the Royal City.

“They were regular customers,” Chew says of the media back in the day, “We were all pals.”

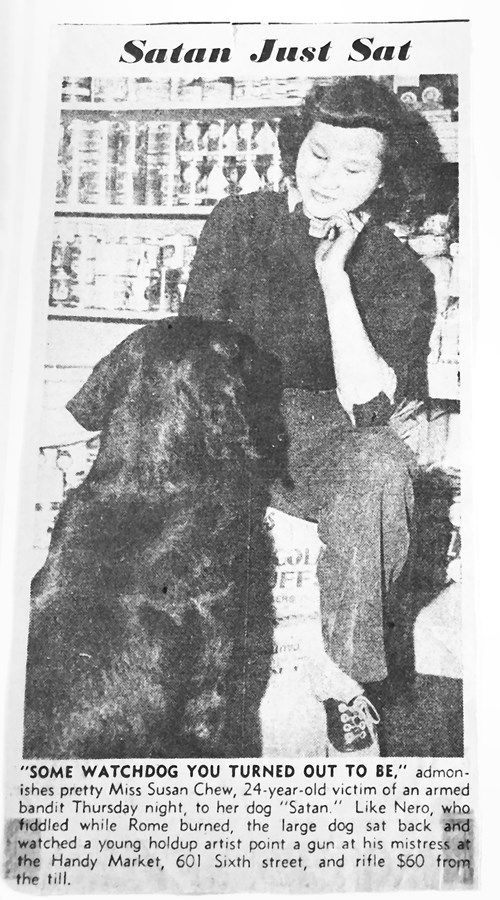

As a well-known local personality, Chew says she provided them with plenty of material, like the time she was robbed at gunpoint at the Handy Fruit Mart while her dog, Satan looked uselessly on.

“The Columbian covered me beautifully,” Chew says, “Every excuse they could get, they would be there with their photographer. I guess I was kind of a colourful character in New Westminster.”

The Bermuda House

When Chew and Thompson decided to find a place together, it was only natural their friends in the press would be invited to the housewarming party.

Finding a place, though, turned out to be not so easy.

“They would have signs on the window,” Chew says of the first few apartments the pair checked out. “We would knock on the door and see if we could rent. And they’d say, ‘Oh, it’s gone.’ ‘Oh yeah, it’s rented.’ We didn’t realize that we were turned down for discrimination when they saw that I was Chinese.”

Finally, in March 1956, they landed a bachelor suite at a “swanky” new apartment block that had just gone up at 1303 Eighth Ave. – the Bermuda House.

(The building, renamed Hillcrest, still stands today, with balconies painted mint-green.)

With the deposit paid, the two women ordered furniture from Eaton’s, and on March 17 Chew hopped into her ’52 Pontiac Catalina and drove to the Bermuda to see if it had been delivered.

It had all right, but the building’s manager, John McIlroy had sent it back.

She couldn’t move in after all, he told her then, because she was Chinese.

What she felt wasn’t anger but searing shame.

“I thought of crawling into a dark cellar, into a hole,” she said. “That’s what came to my mind when I was driving home.”

Like Henny Penny, she said, it seemed to her like the sky was falling.

In a parting blow before she left, McIlroy had advised her to keep quiet about the whole thing since it wasn’t likely she’d get much support from other people in town.

It would take only a matter of days before he – and everyone else in New Westminster – found out just how wrong he was.

In part two of The unbreakable Susie Chew, the Waffle House founder’s plight becomes a national news story.