“And if you ever see Bill around tell him to write to me, and another thing if he doesn’t write soon I will beat his brains out with a teaspoon and play the ‘Warsaw Concerto’ on his teeth with a sledge hammer, that had better scare him into writing.”

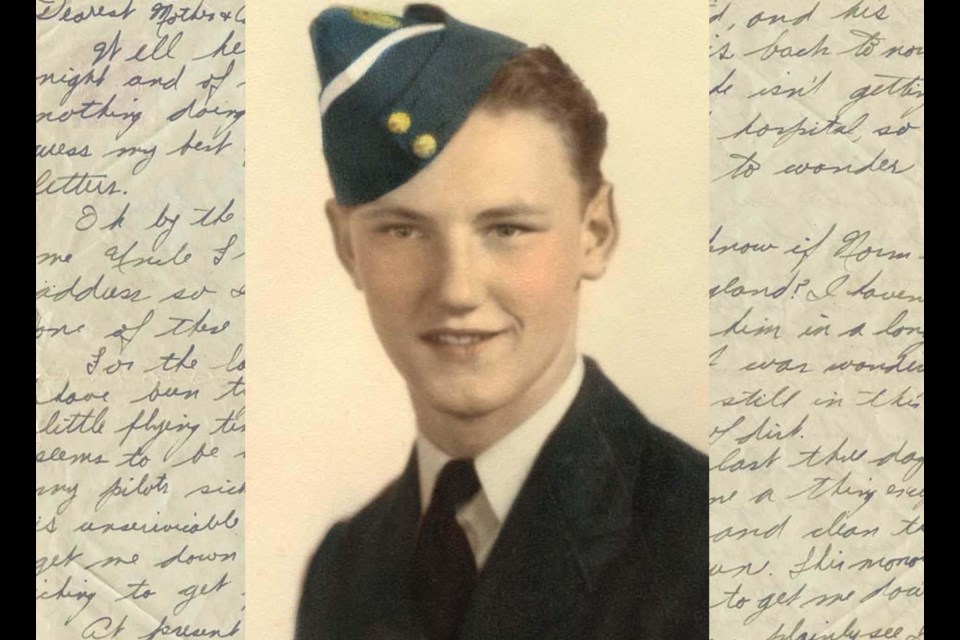

It’s not hard to imagine a little grin on the face of 19-year-old Jack Fitzgerald as he penned those words to his mother, Effie, and kid sister, Ruth, at home in New Westminster.

It was February 1944. Jack had left school two years previously, during his final year at Hugh M. Fraser High School (as Burnaby South Secondary School was known for a short time). He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force, shipped off overseas in December of 1942 and served as an air gunner in RAF 166 Squadron.

As fate would have it, he never got a chance to beat Bill’s brains out with a teaspoon.

Jack would live for another six months and eight days after he wrote that letter home.

He had been on a minelaying mission over Danzig Bay, Poland, with his crew. They were on the return flight when a German night fighter shot their Lancaster down over Denmark’s Jutland peninsula.

On Aug. 30, Effie Fitzgerald got word by telegram that her son had been reported missing in action.

“The Government and people of Canada join me in expressing the hope that more favourable news will be forthcoming in the near future,” wrote Minister of National Defence Charles Power in a letter to New Westminster soon after.

It was not to be.

Flight Sgt. John Ernest Fitzgerald, recipient of the Distinguished Flying Medal for vigilant service and for shooting down an enemy fighter, had died on Aug. 27, 1944. He was buried with the rest of the crew in Denmark.

Letters Home gives Canadians a glimpse into personal war stories

Now, Jack’s letter from Feb. 19, 1944 is making its way back home one more time as part of a national Letters Home campaign.

The Legion National Foundation and Royal Canadian Legion have partnered with HomeEquity Bank on the campaign, which is designed to connect Canadians more closely to the stories of those who fought in the First and Second World Wars.

Replicas of real letters from Canadian soldiers are being mailed out to their originally intended addresses across the country in the lead-up to Remembrance Day.

Jack Fitzgerald’s correspondence is one of two letters making its way to New Westminster this year.

The other is from Pte. Harold Dean, who wrote to his mother from German East Africa, where he served with the British Expeditionary Force in the First World War. Harold was more fortunate than Jack; in the end, he made it home, after bouts of malaria saw him sent back to England to convalesce before his return to Canada in 1919.

The letters provide glimpses into the personal histories of the thousands of Canadians — many of them very young — who left their homes in service of their country.

Canadian Letters & Images Project creates online archive of war experience

Yes, they are authentic letters. They’ve all been sourced through the Canadian Letters & Images Project, an initiative of the department of history at Vancouver Island University. The project, which began in August 2000, is dedicated to digitizing letters, diaries, photographs and other related memorabilia to create an online archive of the Canadian war experience — “from any war, home or battlefront, as told through the letters and images of Canadians themselves,” as the project’s website says.

The letters chosen for the Letters Home campaign are tiny, intimate portraits of the lives of ordinary people living through an extraordinary time, offering small glimpses into life behind the front lines.

For the last three days I have been trying to get in a little flying time but everything seems to be against me. Either my pilots sick or the aircraft is unserviceable it is starting to get me down because I’m just iching to get flying again,” wrote Jack in the letter that’s part of this year’s campaign.

At present my mid upper gunner is in the hospital with a cold, I went to see him tonight and he is looking good, and his temperature is back to normal again, but he isn’t getting out of the hospital, so I’m beginning to wonder things.

Do you know if Norm is still in England? I haven’t heard from him in a long time and I was wondering if he was still in this little bit of dirt.

For the last three days I haven’t done a thing except sit around and clean the occasional gun. This monotony is beginning to get me down.

As you can plainly see I can’t think of a darn thing to write about, but I guess you will be glad to know that I am still alive and kicking at everything and everybody.

How is everybody in the neighbourhood? And if you ever see Bill around tell him to write to me, and another thing if he doesn’t write soon I will beat his brains out with a teaspoon and play the “Warsaw Concerto” on his teeth with a sledge hammer, that had better scare him into writing.

Well it seems as though I can’t think of anything more to say. One of these days I will write a decent letter that is if anything exciting ever happens that I can write about. Well I will sign off now.

Lots of love,

Jack

Family relationships come to light in wartime correspondence

For the curious reader, the single letter leaves questions unanswered — not the least of which is the identity of the unfortunate Bill.

Those who find themselves wanting to know more can delve into the collections at the Canadian Letters & Images Project virtual archive. There, reading through Jack’s correspondence and personal memorabilia slowly builds a picture of a regular teenage boy — with a Hugh M. Fraser High School students’ council card, a YMCA membership, and an affectionate, teasing relationship with the kid sister who noses around about Jack’s love life while spilling the beans about her own romantic adventures.

“I’ve actually met an airman kind of a cute kid but darn it he’s leaving for the East next week. They are having a big blow up at the Commodore so heres where little Ruth steps out with a bang,” Ruth wrote to her brother in May 1944. “Oh well I’ve got the navy around so can fall back when he leaves.”

The correspondence also offers a window into the world of a wartime mother, putting pen to paper to stay in touch with her son across the miles — checking in to be sure he was taking care of himself and that parcels containing much-coveted cigarettes had arrived from home.

Throughout, her mother’s love shines through.

“So until next time be a good boy & take good care of yourself & remember you are always with me in my thoughts and prayers,” she signed off in the spring of 1944.

And, of course, they reveal the ever-present anxiety of waiting for word from overseas.

“Just a few lines to let you know we are all well, & hope you are the same, cant understand why we dont hear from you,” Effie wrote on Aug. 4, 1944. “The last letter we received was dated July 17, so you see it is quite sometime since we have heard, don’t think I am complaining but if you could just find time to drop one line saying you are well that would be allright.”

She didn't know when she sent that letter that her son would be shot down just 23 days later.

Letters support Legion National Foundation's Digital Poppy campaign

“The incredible sacrifices of our soldiers may already seem like a century ago, which makes finding ways to share these letters and the harsh realities they contain with today’s young Canadians all the more important,” Julian said in a press release.

The letters are arriving at their destinations with QR codes that will point people towards the Legion National Foundation’s Digital Poppy campaign, which raises money to help veterans, educate youth on the contributions of veterans, and provide students with scholarships and bursaries.

Find out more about Letters Home and support the Digital Poppy: Here's how

- Want to know about Letters Home? Anyone who’s interested in the project can visit the Letters Home online portal and enter a place name into the search field — the search will show if any letters were sent to or near your chosen location.

- From there, you can donate to the Digital Poppy campaign (in memory of a particular soldier, if you like) or click through to the Canadian Letters & Images Project website to delve into the life stories of the letter writers and to find countless other personal histories of the war.

- You can also simply donate directly to the Digital Poppy campaign.

Follow Julie MacLellan on Twitter @juliemaclellan.

Email Julie, [email protected]