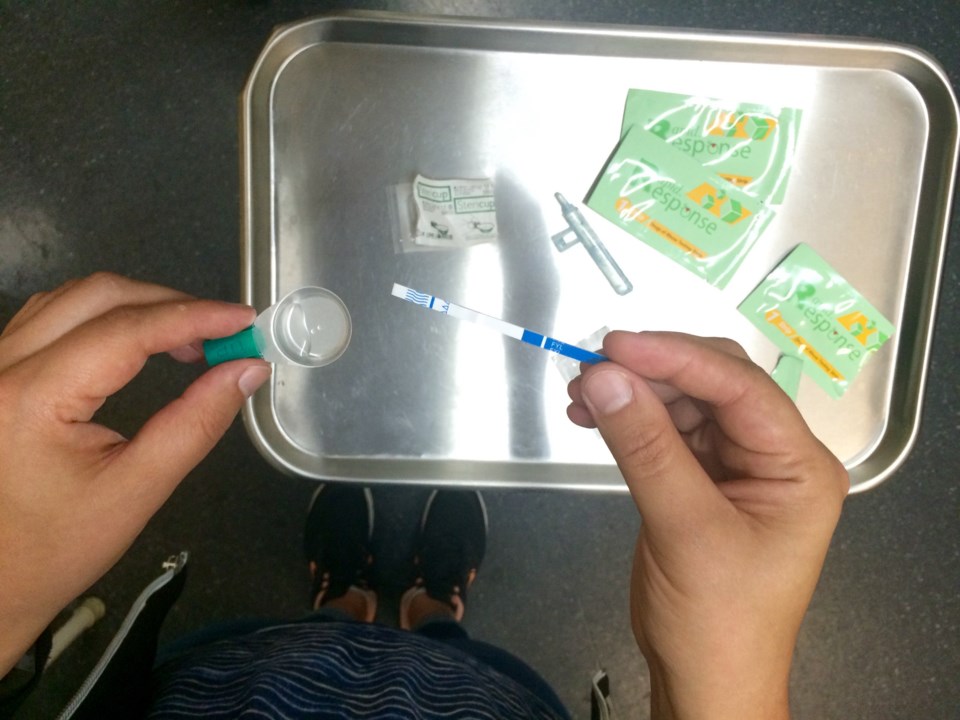

Officials with Fraser Health are looking at ways they can make fentanyl tests more available to people who use drugs after a relatively unsuccessful pilot project last year.

Fraser Health ran a pilot project in several cities, including New Westminster, between Aug. 1 and Sept. 30, 2018, making fentanyl testing available at public health units in the cities. Although the pilot did not see much uptake, the health authority has continued to offer the testing at those sites.

The project intended to reach the “hidden” portion of the overdose crisis – those who often use alone in private residences to hide their substance use from others.

According to Aamir Bharmal, medical director for communicable disease and harm reduction at Fraser Health, 70 per cent of overdose deaths in the region are in private residences.

“We know that there is a population of people who are going to test when they go to an overdose prevention site or a supervised consumption site,” Bharmal said.

“But there are plenty of people who don’t go to those sites, so we wanted to pilot and see whether putting fentanyl test strips in our public health units … would attract other people to potentially get their drugs checked their.”

But data obtained by the Record through a freedom of information request indicate a relatively low turnout. Between July 2018 and June 2019, just four tests were conducted in New Westminster. In the same timespan, just eight tests were performed in Chilliwack, according to the data.

Surrey and Abbotsford had 95 and 60 tests, respectively, performed between July 2018 and June 2019.

Bharmal acknowledges the low uptake, but he added keeping the testing available at the public health units still offered some benefits.

“Speaking with our nurses and the staff who were involved with seeing the clients, they had good conversations with a lot of people. Some of them didn’t know about naloxone or they were able to get trained about it,” Bharmal said.

“There were a lot of pieces where we were just able to connect with people, which was helpful in a lot of ways.”

Bharmal said Fraser Health is working not just through its public health units but also through community partners out in the field.

But he said Fraser Health has been hesitant to make fentanyl test strips publicly available for free like naloxone kits. Bharmal said the main concern is that drug users may take a false sense of security from the tests.

The strips only test for fentanyl and its analogues (including carfentanil), but they don’t test for other drugs, like benzodiazepines, which have, this year, become more commonly found in opioids.

Bharmal acknowledged similar concerns have arisen from nearly every other type of harm-reduction measure, from naloxone to overdose prevention sites – concerns that haven’t borne out with those other measures.

Still, Bharmal said the health authority intended to take a phased approach to making fentanyl testing available, saying it can help officials determine who is using it, how it’s being used and what the unintended consequences may be and how to handle those.

“That’s really what we’ve seen with naloxone,” Bharmal said, noting it would have started with health-care professionals before being available to harm-reduction and similar workers and finally to the general public.

In terms of hastening the process of getting fentanyl testing more publicly available, Bharmal said Fraser Health is keeping an eye on studies currently being done by the Vancouver Coastal and Interior health authorities on the matter.

He added one of the barriers to quickly rolling out harm-reduction measures is public perception, saying it takes time to convince communities the measures are not “enabling” drug use.

“We’re trying to minimize the harms, recognizing that this is a contaminated drug supply that we’re dealing with,” he said.