Burnaby wants to keep raw sewage out of local waterways by separating the last of its combined sewer and stormwater pipe system.

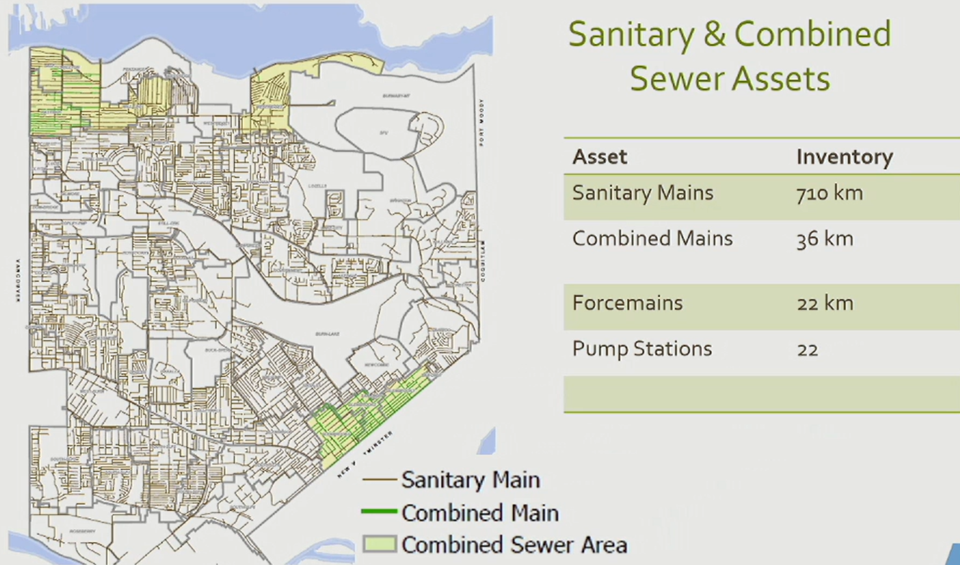

Just 36 kilometres of combined pipes remain in Burnaby, but there’s work to be done beyond that, according to staff at a presentation on combined sewer separation March 24.

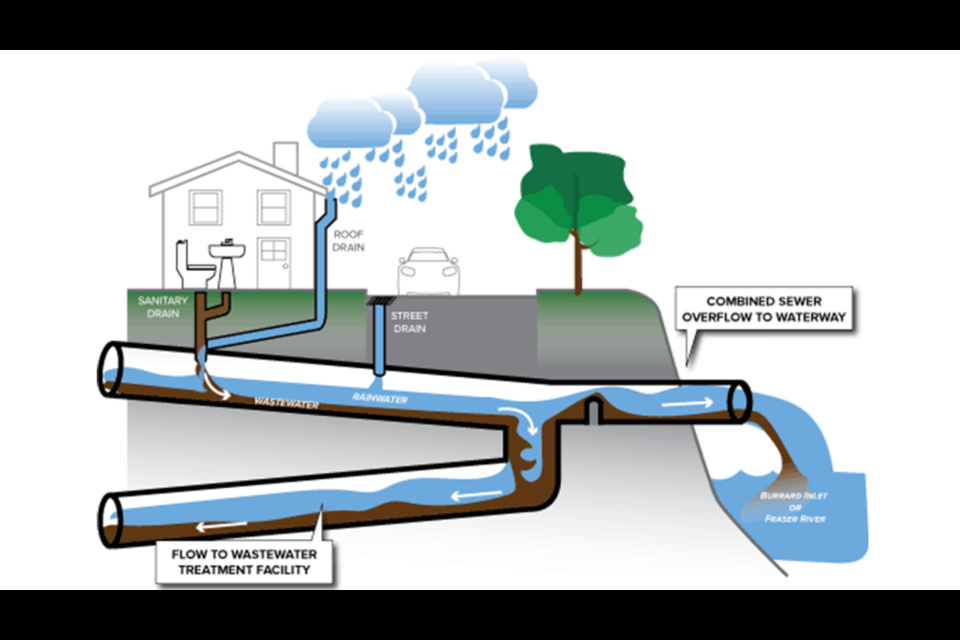

A combined sewer is a single pipe that carries sanitary sewage (domestic waste from homes and industries) and stormwater (rain that hits the ground and runs along the streets), according to Ron Weismiller, senior operations engineer specializing in waste and water.

The lower half of the combined pipe fills with sewage, leaving the upper half for stormwater, said Weismiller, who’s been with the city for 25 years.

The sewage flows through the pipes to treatment plants at Iona Island or Annacis Island.

But on rainy days, the pipes can reach capacity and spill the combined flow (including untreated sewage) into the Burrard Inlet or Fraser River.

These overflows have a negative effect on the environment, according to the city’s storm and sanitary sewer website.

The city has measured more than 100,000 cubic metres of overflow per year, according to Weismiller.

The city wants to separate the last 36 kilometres of its combined sewer system pipes so the sewage can go straight to a treatment plant through its own dedicated pipe, and the stormwater can go directly to lakes, rivers or the inlet.

Burnaby originally used a combined sewer system, but by the late 1950s and 1960s, as sewage treatment plants came into play, the city began building a separated system.

The city has already spent nearly $40 million separating almost 50 kilometres of the original 85 kilometres of combined sewer inventory, according to the city’s website.

Which parts of Burnaby have a combined sewer system?

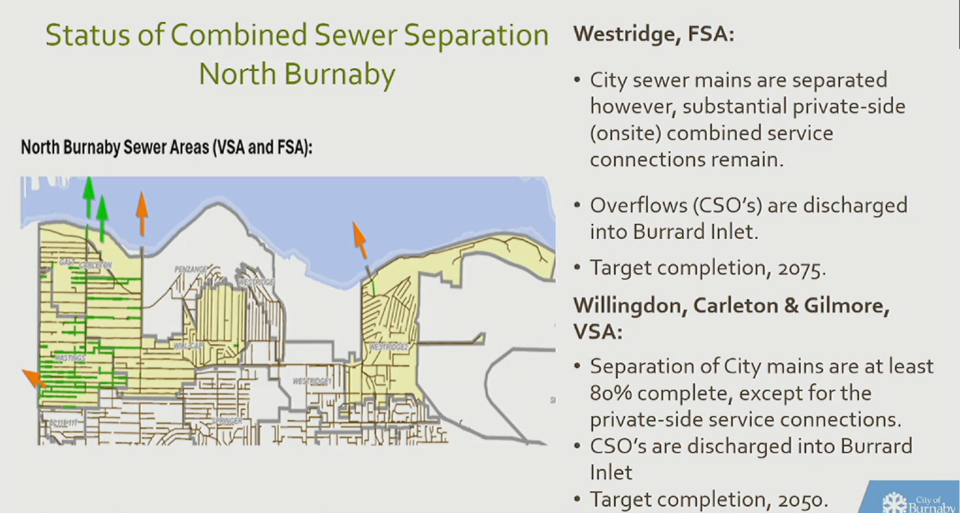

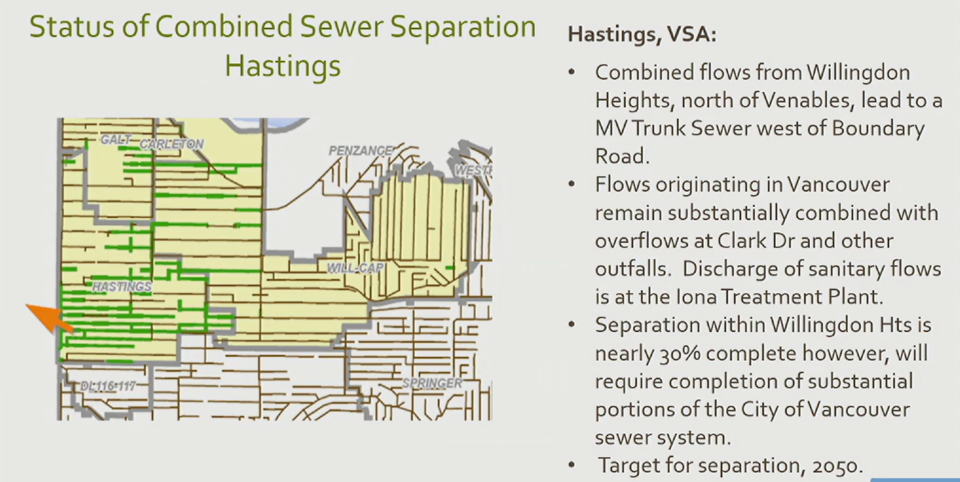

The three main areas that still use a combined system are Glenbrook, Westridge and Hastings, according to Weismiller.

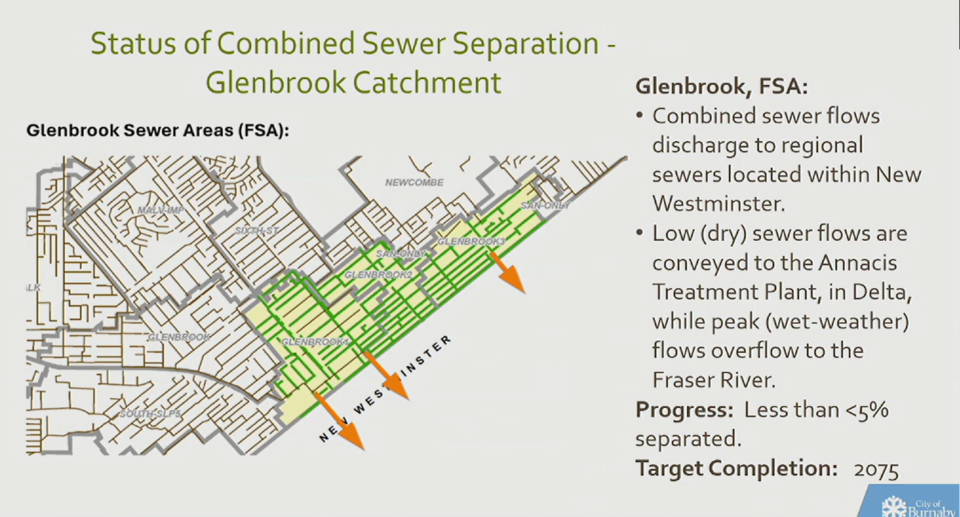

Separating the pipes in Glenbrook, immediately north of New Westminster, will require a coordinated effort between Burnaby, New West and Metro Vancouver, as the combined sewer flows into a trunk line owned by Metro Vancouver.

Less than five per cent of Glenbrook is separated.

Leon Gous, the city’s chief administrative officer, noted the topography in Glenbrook won’t allow the city to take the stormwater anywhere else than down into New West, which currently has a 100 per cent combined sewer system.

Mayor Mike Hurley suggested “it would kind of be a waste of time” to separate the Burnaby side until work is done on the trunk side in New West.

The city’s target to finish the separation in Glenbrook is in 2075, and the rest of the areas in 2050.

In North Burnaby, one specific outfall used to spill about 100,000 cubic metres per year, but when recently measured, it was down to 30,000 cubic metres.

“I view that as at least a small victory in the interim,” Weismiller said.

What are challenges to separating the sewer and stormwater pipes?

Weismiller said the barrier to separating the last 36 kilometres is the financial cost.

It could cost between $2,000 and $2,500 per metre to separate the lines.

The city has historically separated as much as two or three kilometres of sewer per year, according to Weismiller.

May Phang, general manager of engineering, noted separating sewers is a much more intensive process than just replacing old or leaky pipes.

“When separating, the scope of doing that work essentially blows out the entire road,” she said.

“And so, with combined sewer separation work, we are essentially restoring the entire width of that road which adds to the capital cost.”

One challenge for the city will be hooking up homes in areas with combined sewers to the new separated sewer lines.

Weismiller said the plumbing fixtures are hooked to a single pipe, connected to the home’s roof water leaders and on-site drainage.

This private side of the sewer separation includes about 4,000 service connections that are considered combined.

The city also has to deal with “inflow and infiltration,” which is when leaky sewer lines draw in excess water and overwhelm the sewer and can create sanitary sewer overflows in homes and on the street.

Gous noted one of the city’s biggest issues is private residents illegally redirecting water into the sewer system.

A resident will show the city’s plumbing inspector they’re discharging water onto their property — but “no one loves that,” Gous said, because it results in “soggy, soaking lawns for the entire winter.”

“The minute we leave the property, they get a plumber in to connect that back into the sewer line.”

Resident incentives?

Coun. Alison Gu asked about offering incentives to residents, such as offering residents free plastic redirection spouts or absorbent plants to redirect rain.

But staff said those solutions pose other problems.

Gous noted the City of Vancouver (where he said the cost of sewer separation is “astronomical” to the point of being “unaffordable”) is desperately seeking alternative methods to ease the burden on the system — but the region is a rainforest.

He noted various tools, from rock pits to gravel layers under lawns, can work well for the first storm, but fill up quickly.

The region doesn’t have enough dry periods once the rainy season starts.

“When it gets wet, it’s wet.”

To read more about Burnaby’s sewer system, check out the city’s website, the staff presentation or listen to the presentation here.