In a city with one of the highest life expectancies in the world, how long the average person lives in Metro Vancouver varies widely from neighbourhood to neighbourhood — and that inequality is only growing, a new study has found.

The results of the UBC-led research, published in the journal Health and Place, show life-expectancy gaps of up to several decades in neighbourhoods fewer than five kilometres apart.

In some neighbourhoods, such as Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, mean male life expectancy dropped to 60 years, ranking it alongside developing countries that have faced years of war (i.e. the Democratic Republic of the Congo). In Vancouver’s more affluent neighbourhoods like West Point Grey and Kitsilano, the average age someone lived to was almost 30 years higher.

“Even when we cut the extremes, we’re still seeing gaps of almost 10 years,” says lead author Jessica Yu. “It does mirror a lot of the poverty trends that we’ve seen.”

Unlike any study before it, Yu’s research tracked life expectancies across a quarter century, from 1990 to 2016. The team tracked death by blending mortality data from the province, census track data from Statistics Canada and other sources of information on socio-economic deprivation.

As seen across the world, females had a higher life expectancy than males. But it was how inequality changed over time between neighbourhoods where some unexpected trends emerged.

Between 1991 and 2001, the life expectancy gap between neighbourhoods declined. Since then, evidence that inequality was getting better evaporated. By 2016, the last year of the study, the divide in life expectancy for males living in different Metro Vancouver neighbourhoods widened more than at any time in the previous 27 years.

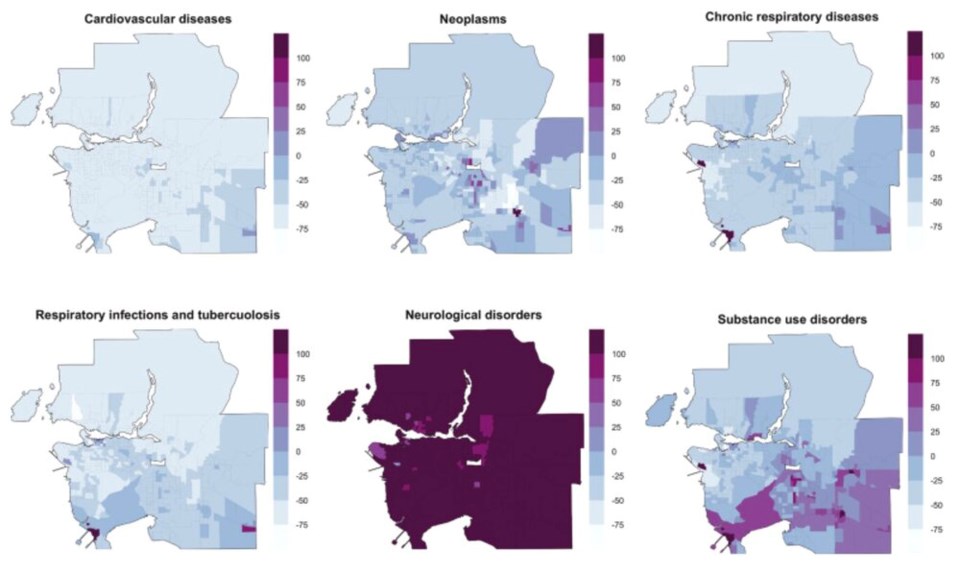

Some of the biggest drivers of life expectancy inequality emerged among males with prostate cancer.

Yu says her team also found up to 17-fold discrepancies in mortality due to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, and up to a 10-fold gap for maternal neonatal disorders, and a nearly six-fold difference between neighbourhoods when it came to injuries from transportation.

Huge divides between neighbourhoods were also found when it came to death due to heart disease, lung and pancreatic cancer and stroke.

Without measuring it, Yu suspects that’s likely due to gaps in access to health care for things like cancer and STI screening, as well as better transit and more green spaces in some neighbourhoods.

“We can't exactly say what are driving these trends,” says Yu. “But logic says that if you increased access to health care, if you increase capacity and language and understanding about the screening… that's obviously going to reduce your risk for mortality from these different cancers.”

She adds: “We hope we can explore these types of questions… we're hoping that it can be linked to you know, vulnerability data, exposure data, like extreme heat.”

Because Canada's 2021 census data hasn't been released yet, Yu’s study doesn’t capture the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. She says work still needs to be done to track that mortality data, along with the rising toll from the opioid crisis and climate change.

How race or ethnicity affects life expectancy from one neighbourhood to another is another blind spot, according to Yu. Across Canada, past research has found life expectancy to be lower among First Nations communities by an average of 16 years; and one study found First Nations in Canada had some of the highest rates of death from suicide, pneumonia and influenza when compared to Indigenous communities in New Zealand or the United States.

That shouldn’t stop local politicians and other leaders from taking action on the findings, says Yu.

Public and policymakers are usually fed average life expectancies at the national, provincial or city level. What this research does, says Yu, is unmasks what’s really going from one neighbourhood to the next.

“Health matters at the neighborhood level,” she says. “It just really requires a lot of cross-collaboration on all levels of governance, not just provincial, national, but also municipal planners, so that we can allocate the right types of services and resources to the neighbourhoods that are most in need.”