HALIFAX — After almost a year of leading Atlantic Canada's largest non-profit care home through the COVID-19 crisis, Janet Simm sees "elements of hope" in 2021.

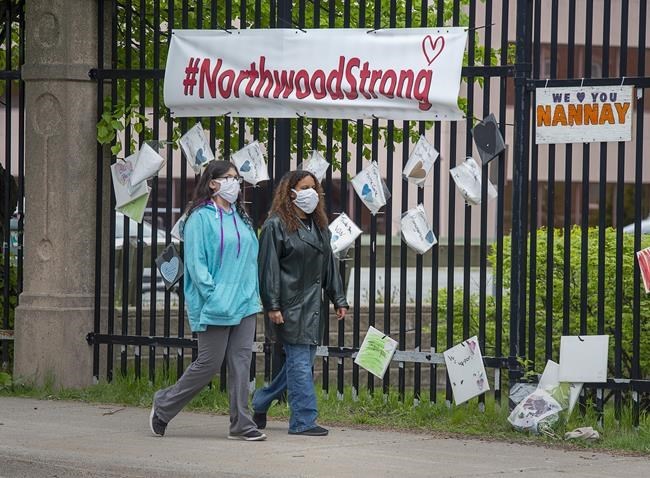

"Vaccinations are the light at the end of a very, very, very difficult tunnel," the chief executive of the Northwood long term care facility — where 53 of Atlantic Canada's 77 pandemic-linked deaths occurred — said in an interview earlier this week.

"But we can't lose sight of all the prevention measures we must keep in place."

About 300 of the roughly 1,700 staff at the Halifax-based facility have had the first of two required doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, she said, adding that the goal is to have all staff vaccinated by March.

Unlike Quebec, which started vaccinating long-term care residents at the same time as staff, Nova Scotia decided to inoculate long-term care workers first. But after Health Canada on Wednesday approved the Moderna vaccine — 3,700 doses of which are expected to arrive in Nova Scotia later this month — Simm said residents could start getting vaccines early in the new year.

But despite that good news, some advocates for elder care say deep, underlying problems — ranging from insufficient staffing to crumbling facilities — must be addressed to avoid similar tragedies.

Northwood's COVID-19 outbreak led to a review last fall of the home's procedures, while a separate government investigation looked at infection control in all care facilities across the province.

In September, Nova Scotia announced it was spending $26 million this fiscal year and $11 million over the next two years in the long-term sector for such things as mobile, infection-control response teams and for more cleaning staff.

Yet, while the province takes steps to deal with the immediate threats of the pandemic's recurring danger, the director of the Nursing Homes of Nova Scotia Association fears the will to create a fresh vision for senior care is lacking.

"There's been acknowledgment by experts and even Prime Minister Trudeau that the failure of long-term care in this country provides us with the opportunity to rebuild in a meaningful way," Michele Lowe said in an email.

"The investments that have been made in Nova Scotia have been well received and appreciated, but it is just the beginning of a deeper, fundamental investment in the vision for long-term care for Nova Scotia."

One of the key pushes has been to end the use of shared rooms, which last fall's government review said aided the spread through Northwood.

At the downtown Halifax Northwood campus, the number of residents has fallen from 485 to 385, and the practice of sharing rooms has largely stopped, Simm said. "We've successfully prepared for a second wave," she added, noting there have been no infections at the facility since May.

She said Northwood has also increased the number of designated caregivers — usually a patient's family members — through a training program that teaches them how to avoid spreading the virus.

A spokeswoman for the Health Department said Wednesday the province is receiving $15 million in federal funding for infection control, staffing and for other assistance to the long-term care sector.

That money, Lowe said in a telephone interview on Wednesday, should be spent on improving infrastructure. "Some (buildings) are more than 50 years old and have no ventilation, so it's certainly good to hear some funding is available," she said.

She said she wonders, however, whether governments have fully understood that the wave of sick and vulnerable elderly in need of care is growing rapidly. "When we look at eight years out, the demand across Canada will double and the amount of persons with dementia is significant," she said.

"There are so many things we need to be able to tackle and we don't feel that we've had the leadership and grit to get this done without significant changes in mindset."

Meanwhile, Janet Hazelton, the president of the Nova Scotia Nurses' Union, says the law governing special care homes in the province hasn't been reformed because the legislature hasn't sat for a full session in months.

"We're continuing to apply pressure," she said. "COVID-19 has shone a light on the lack of hours of care residents receive."

The union — which represents about 1,400 nurses — has argued for an average of 4.1 hours of care per resident, per day, including 1.3 hours of nursing care. That would mean, the union says, adding about 600 nurses and 1,400 continuing care assistants.

The nurses union said in a study released earlier this year that the roughly 7,000 long-term care residents in the province receive about 3.4 hours of care per day. Hazelton said she hopes any federal money sent to the provinces will come with conditions it be spent on increasing care.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 24, 2020.

Michael Tutton, The Canadian Press