Say this about Olive Bailey: She could keep a secret.

It wasn’t until 20 years ago that the Victoria woman finally revealed her Second World War past to her husband, and even then she did so only after an old Bletchley Park colleague blurted out “Have you told him yet?” in his presence.

The Bletchley codebreakers’ story is well-known now, though, thanks to television’s The Bletchley Circle and films like The Imitation Game and Enigma.

Those shows tell the tale of how a team led by the brilliant Alan Turing, toiling at the super-secret British cipher centre at Bletchley, a Victorian mansion 60 kilometres north of London, used massive computing machines to break what the Germans believed to be unbreakable codes.

Deciphering intercepted enemy communications, these bright young minds helped change the course of the war — though it would be decades before the world would learn about their spy games, the players staying quiet until the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act were lifted. One of those players was Bailey. “I kept my secret for a long time,” she said in 2016. “You just put it away in one compartment of your brain.”

Olive died on Sept. 23 at the age of 101, another member of the Greatest Generation gone.

She was born to Geoffrey and Lillian Gore in 1921 in Berwick-on-Tweed, on the Scottish-English border, but grew up in London, where Lillian became a single mother after her husband died.

Olive earned a math degree, but after the war broke out, the 19-year-old found herself working in a London factory that had gone from making buses to producing sections of Halifax bombers.

Then, as she told the father and son team of Jim and Nic Hume in a 2007 Times Colonist interview, her life changed.

They told the story like this: “Out of the blue came a letter requesting her to report to an office in Covent Garden where she was interviewed, quizzed about crossword puzzles — ‘which I was quite good at’ — and offered a job. She accepted, was sworn to secrecy, handed a railway pass from London Euston to Bletchley Park and a telephone number to call on arrival. She was now working under the umbrella of MI-6 — the Secret Intelligence Service.”

Hush hush, of course. Olive could only say that she was involved in some sort of war work. “My mother didn’t even know that I was at Bletchley,” she would say.

About 9,000 people worked on the Bletchley project, though few were as close to the centre as Olive, who was stationed in what was known as Hut Six. “Hut Six, known as ‘the elite hut,’ was where army and air force code breakers worked,” the Humes wrote. “Hut Eight was navy. Hut Three, ‘the holy of holies,’ was where ‘hot’ deciphered intercepts were filed and forwarded to Britain’s War Cabinet and Churchill.”

Turing et al advanced the work of Polish cryptanalysts who made the first steps to unlocking the secrets of Germany’s Enigma coding devices in the 1930s.

The Bletchley people got a huge boost when a typewriter-like Enigma machine was captured from a German U-boat that had been depth-charged to the surface. (The Royal Navy boarding party was led by a courageous 20-year-old officer named David Balme, the brother-in-law of Cobble Hill’s Jenny Balme.)

At Bletchley, Turing’s codebreaking machines were critical — and massive, rising almost to the ceiling. “One of the computers they built was called Colossus and had huge wiring on the outside of it,” Bailey told the TC’s Sandra McCulloch in 2012. “I had to stand on chairs [to use it]. It was like plugging in light bulbs.”

How secretive was the work? Olive offered some insight a few years ago at one of the annual events at which Winston Churchill fans, led by columnist Les Leyne, enjoy a toast around a hawthorn tree that Britain’s wartime prime minister planted in Beacon Hill Park.

She told the crowd of being with Turing in a room where the work was so sensitive that even Churchill, on a tour of the facility, wasn’t welcome. “So Alan saw Winston coming and stretched his leg out and kicked the door shut.”

Olive’s son Nigel Bailey says his mother remembered Turing as good-humoured but famously distracted, to the point that he would chain his coffee cup to the radiator to stop himself from losing it. (She also told the Humes of another “boffin” who was so lost in thought during a tense period that he tried to smoke his dinner. “He was pacing up and down, pipe in one hand, a crushed sandwich in the other. He paused, stuffed the sandwich into his pipe and tried to light it.”)

The work was intense, and the consequences serious. Years after the war, it was reported (and subsequently disputed) that Churchill, after learning of an impending air raid on Coventry, chose not to mount a defence that would have tipped off the Germans that their code had been broken. That haunted Bailey. When Jim Hume told her he was in Coventry that terror-filled night, she said she was sorry and her eyes fill with tears.

At the same time, Olive had to contend with raids on London. “We were bombed and bombed and bombed,” she told McCulloch. “The back of our house was bombed and they replaced it with plywood. I really don’t think we could have gone on much longer.”

Olive would later talk about an air-raid siren going off one day in 1940, when she still worked in the factory. Like others there, she waited until rooftop spotters saw the approaching German planes before seeking cover. (“We never went straight to the shelter. You’d never get any work done.”)

Except when Olive tried to leave, a piece of jewelry she was wearing, a pin that spelled her name in gold wire, became trapped in the keys of her typewriter. She was still in the building when the bomb went off. “I was buried under the rubble for five or six hours.”

When she finally got home, caked in dust, her mother said: “There you are, dear. I thought you were dead.”

Actually, being trapped in the typewriter might have saved her life. Those who fled ahead of her were caught in the explosion.

Considering such experiences, catching the train from the embattled capital for bucolic Bletchley each day must have been a relief, Nigel says. “It obviously was a respite from the Blitz in London.”

He still marvels at what his mother and her Bletchley colleagues endured. “These were all young women, 19 and 20,” he said last week. “They really went through something, and it formed what they were for the rest of their lives.” Their experience made them strong, confident in their morals and opinions.

The Bletchley story remained largely unknown, though. After the war, Turing was prosecuted for homosexuality, which was then illegal. He died in 1954 at age 41 after eating a cyanide-laced apple. It wasn’t until 2009 that he received a posthumous apology from the British government. His likeness was chosen for the 50-pound banknote a decade later.

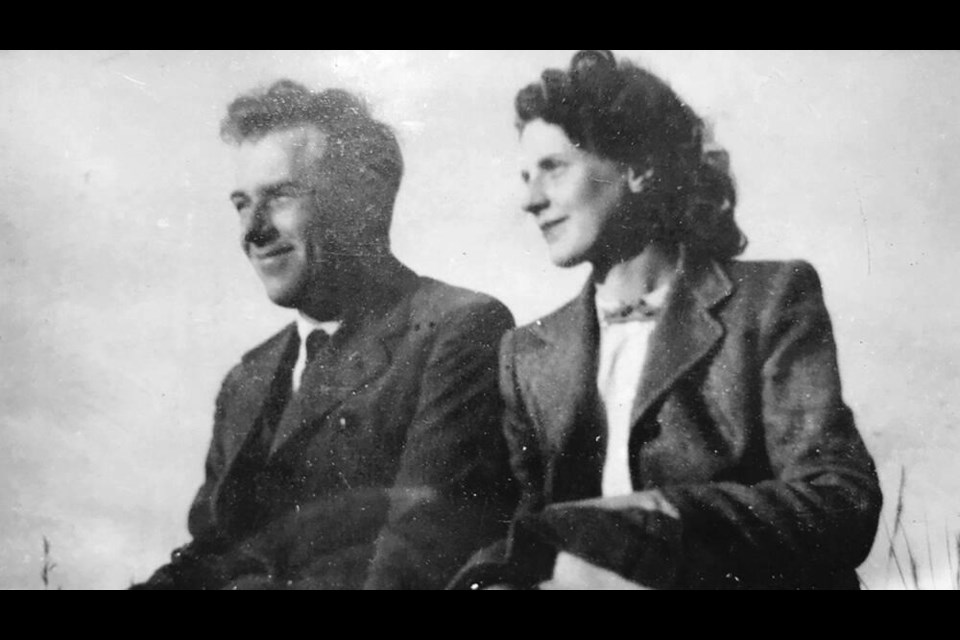

Olive married eye surgeon Norman Bailey in 1946. In 1951, they left London for the cold and culture shock of Saskatchewan, where they became good friends with neighbours John and Olive Diefenbaker. The Baileys made their way to Victoria in 1965. Norman died two years ago.

Here, Olive wasn’t the only one with a Bletchley connection. In the past decade, the Times Colonist has carried the obituaries of half a dozen women who worked on the project.

In 2019, the obituary of Victoria’s Marcia Williams, who worked at a Bletchley substation outside London, described how she, like Olive, refrained from telling her husband about her work until the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act were lifted.

In 2021, the obituary of Greta (Molly) Morgan spoke of how she worked at Bletchley in the same hut as Turing; later in the war she worked as a linguist intercepting and translating communications from U-boats and German fighter pilots.

Nigel Bailey says he struggles to convey to younger Canadians how special those of his mother’s generation — children of the Depression, reaching adulthood just as war descended — were, how much history is gone when they vanish.

“They were a group of very young people, dealing with an existential threat. It strikes home when you lose one of them.”

jknox@timescolonist.com

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: letters@timescolonist.com