Ivan and Peter Koubek’s father has just died, but neither seems willing to talk much about it, let alone to one another. After all, it’s not like the two brothers are even friends.

Peter, the eldest by a decade, pities his awkward, 22-year-old brother, a competitive chess player whose prowess for the game hasn’t done much to build his social skills or self-esteem. But after meeting Margaret, an older woman who’s emerging from the shadow of her own crisis, Ivan’s life has begun to blossom — and the same cannot be said for Peter. A human-rights lawyer — once optimistic, now jaded — Peter’s self-medicating and can’t stop sabotaging his relationships with Naomi, a wry, carefree college student, and Slyvia, his former flame and longtime love.

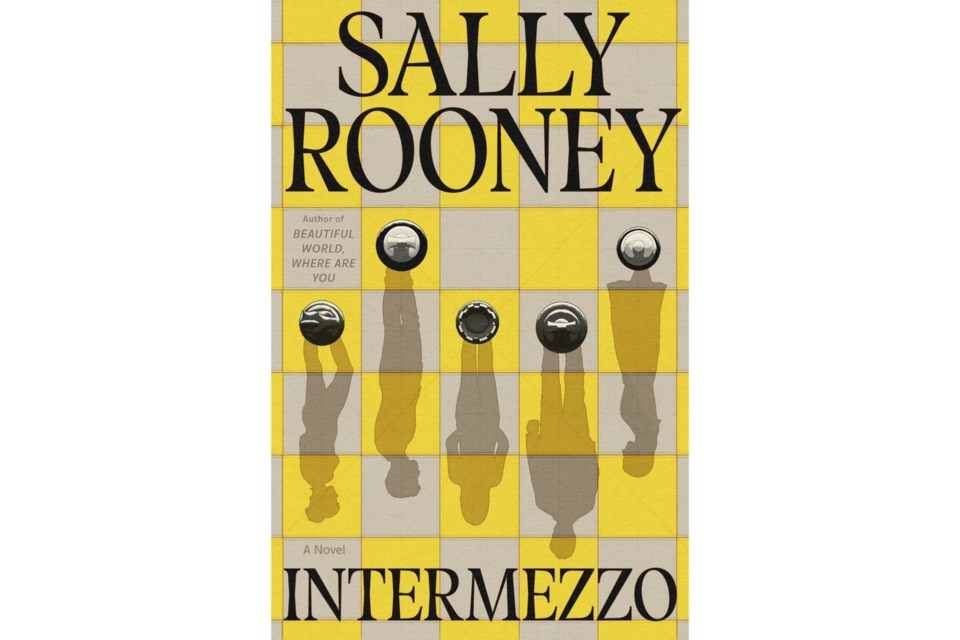

The days after tragedy are often hard to navigate and “Intermezzo,” the fourth novel from Irish author Sally Rooney, is a portrait of grief not fully internalized. In her astutely intimate style, Rooney wades through the convoluted emotions that follow tragedy: certainly heartache, but also relief and longing, guilt and joy, all on the cusp of transformation.

In sketching the contours of her characters, Rooney alternates between the perspectives as she did in her last novel, “Beautiful World, Where Are You.” Her dialogue, characteristically bare and without quotation marks, lends a distinct musicality to her prose.

As Peter’s mind becomes untethered by pills, Rooney’s close third-person voice dances over the line of spoken and unspoken, slurring together in long, drawn-out paragraphs as he wanders the streets of Dublin — meandering sentences broken by sharp staccatos of self-pity.

Ivan meanwhile, follows the well-trod path of other stunted men, intelligently methodical yet rambling, grasping at emotions with insufficient words. These instances of almost are where Rooney shines. She teases out near-ruptured emotions never fully felt by the conscience, untethering them from reality for our voyeuristic pleasure.

When Ivan first meets Margaret, Rooney notes that he has “an involuntary mental image of kissing her on the mouth: not even really an image, but an idea of an image, sort of a realization that it will be possible to visualize this at some later point.”

Margaret herself is struck by the uncanny sense that “life has slipped free of its netting” following her first encounter with Ivan. “It means nothing,” she thinks, then quickly course corrects. “That isn’t true: it means something, but the meaning is unfamiliar.”

This is often the meter of metamorphosis, the mundane swirl of emotions flirt past, illegible and unrealized until they inevitably burst, fully formed and so wholly overwhelming that they cannot be contained. And it is at this in-between, restrained and circumspect, where Rooney situates her novel — consider the title.

Intermezzo, an unexpected move in chess that interrupts the typical sequence of exchanges, is a risk that upends the game’s perceived balance, raising the stakes.

In the tense, messy contradictions of communal grief, Rooney weaves together beautiful whole cloth.

___

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews

Curtis Yee, The Associated Press