TORONTO — Before Allan Dugas moved into long-term care, he feared he'd be forced to share a bedroom in an impersonal, institutional building, where a regimented schedule would dictate when he ate and what time a staff member would "barge in" to get him out of bed early every morning.

So after he was hospitalized for a fall, he chose to be discharged to a facility that health-care workers told him they'd be comfortable placing their own parents — a "small care home" in Digby, N.S., made up of 10 houses, each with nine residents and a small group of designated staff.

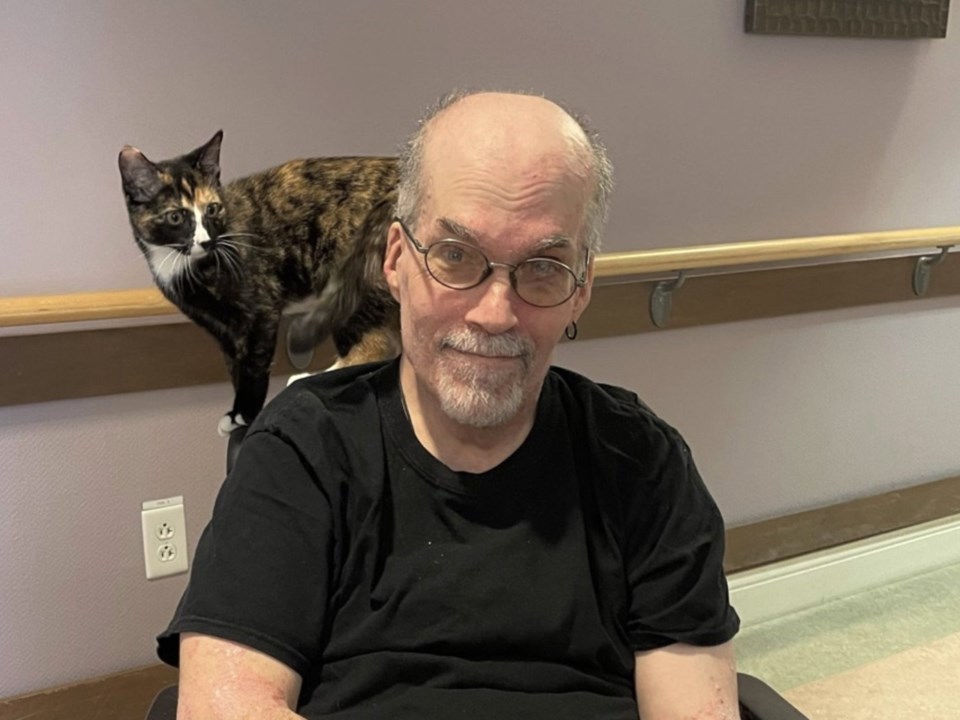

Dugas called the last four years of his life at Tideview Terrace "wonderful."

He has his own bedroom and bathroom, and the freedom to get up and go to bed when he wants. He even has a drum set in his bedroom, where his only roommate is his cat, Jones.

Dugas shares a kitchen and living room with eight other housemates, and said ”there's a lot of laughter here."

"Life isn't over, it’s just a different chapter,” said 59-year-old Dugas.

”It’s about respect and autonomy and making this our home."

Dugas was born with spina bifida that weakened him as he got older to the point he needed full-time care. He's the youngest resident of the home and estimates the majority are between 65 and 95 years of age.

Tideview Terrace is a complex divided into interconnected but separate houses but the small care home model can be applied in different ways, ranging from single houses integrated into residential neighbourhoods to larger buildings, where a floor might be designated a single "household" for several residents.

However they're designed, their hallmark is having just 10 to 12 residents per household and a more comfortable home-like environment, instead of the more commonly seen hospital-like institutions.

Each resident in a small care home has their own bedroom and bathroom, and their household group shares a kitchen and living area.

In a report released last week, the National Institute on Ageing called on all levels of government to make small care homes the standard across Canada, pointing to a survey it did in 2021 that found nearly all respondents said they'd "do everything they could" to avoid living in an LTC home.

Co-author Dr. Samir Sinha said that since it's not realistic for all seniors to remain in their own homes, the next best thing would be better quality long-term care in home-like settings — especially since the majority of residents are likely to have some form of cognitive impairment.

"When you start thinking about what's ideal for a person living with dementia, it's not living on a unit with 32 other people and staff ... a whole bunch of different faces all the time," said Sinha, a geriatric specialist at Sinai Health in Toronto and the NIA's director of health policy research.

Small care homes in Europe, the United States, and the handful that exist in Canada report more one-on-one care for residents, as well as greater staff satisfaction that leads to less employee turnover, the report said.

The U.K. and Europe have largely shifted to developing small care homes, while "North America has emerged as an outlier" in its preference for "large institutional care settings that resemble lower acuity hospitals rather than home-like settings," it said.

In small care homes, each resident largely follows their own daily sleep schedule and has flexibility around meals and activities, in contrast with traditional "task-oriented" homes that seek efficiencies through regimented wake and sleep times and mass meals delivered in large dining rooms, Sinha said.

In addition, each household has a small, dedicated staff of personal support workers and other front-line workers, providing consistency and more personal care based on knowing each resident's likes, dislikes and habits.

Everyday tasks such as cooking and cleaning in smaller settings are often split between staff members and can serve as opportunities for more interaction with residents, Sinha said. For example, residents can help prepare meals if they're willing and able.

More specialized staff — including registered nurses, physiotherapists and dietitians — are shared by all the households.

The National Institute on Ageing's report said more research is required to determine if small care homes are actually more cost-effective than traditional long-term care homes, but said "the initial studies are promising."

Debra Boudreau, Tideview Terrace's administrator, said that's been the case at her facility, which transformed into a small care home from a traditional institution in 2011, a few years after Nova Scotia became the first province in Canada to incorporate small care home design.

Boudreau, who has worked there for almost 20 years, said the small care home structure doesn't cost any more to build and run than other public long-term care facilities in the province, since all homes are allocated the same funding per resident — it's just used differently.

"We had a certain footprint that we needed to work within in order to meet the design guidelines, and so we really maximized as much resident space as we could," Boudreau said.

That meant allocating less space to administration offices and more to living space.

"Yes, we work here, but the primary purpose of the facility is to be a resident’s home," she said.

The small care home model also excels at infection control, which became very clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, Boudreau said.

While the virus tore through many long-term care homes and killed thousands across Canada, Tideview Terrace was largely spared because "we could close a house, isolate everybody, keep consistent staffing," she said.

The home didn't have a COVID outbreak until two years after the pandemic began and ultimately had three deaths.

In addition to Nova Scotia, six other Canadian jurisdictions — Alberta, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut — have supported the "mass development" of small care homes, the National Institute on Ageing report said. Other jurisdictions have made varying commitments to the model.

Ontario is the only province where "no current initiatives have been identified supporting the development of small care homes," the report said.

The province's ministry of long-term care said in an email that it "provides flexibility to operators to propose smaller scale projects as there is no minimum bed requirement for a new or redeveloped long-term care home in Ontario."

"Ontario will continue to encourage construction of projects, while providing operators with the flexibility to meet the needs of their communities, that meets the demands of Ontario's growing population," spokesperson Mark Nesbitt said on Friday.

Advocates argue provinces and territories have an obligation to actively prioritize small care homes.

"Somehow we need to change people's mindset on what it means to age when somebody can no longer live (at home)," Boudreau said.

"It's not OK to just keep warehousing people in traditional institutions.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 21, 2025.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

Nicole Ireland, The Canadian Press