It’s a refrain that voters heard repeatedly leading up to the election, not just in New Westminster but across B.C.: If you want to get rid of the B.C. Liberals, you’d better vote NDP.

New Democrat supporters pounded the pavement to get the message out that a vote for the Greens would be, in essence, a vote for Christy Clark’s Liberals.

But now that election night has come and gone, the question remains: Was that really the case?

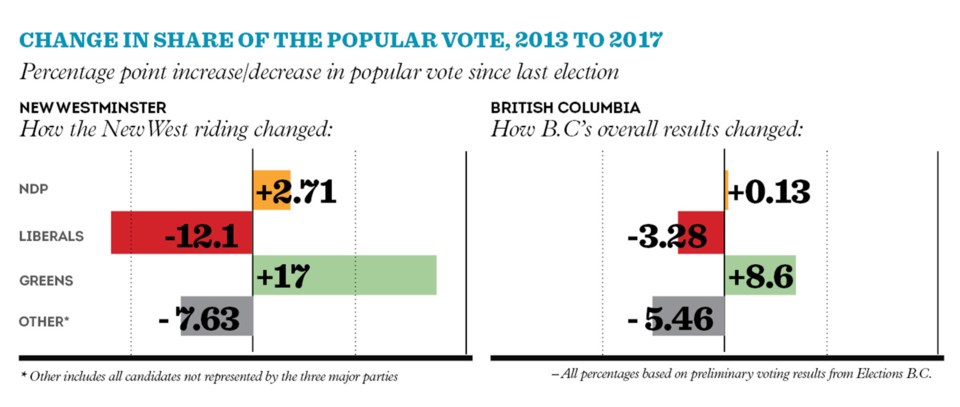

The spectre of vote-splitting was raised early in New Westminster, when school trustee Jonina Campbell entered the race for the Greens against NDP incumbent Judy Darcy. And, in fact, Campbell raised the Green vote percentage by a significant margin, from 8.35 per cent in 2013 to 25.36 per cent this time out.

But here’s the catch: at the same time, NDP support in the city didn’t drop. In fact, Darcy raised her popular vote from 48.84 per cent in 2013 to 51.55 per cent Tuesday night.

“I was scratching my head half the night trying to figure out who the Greens were going to damage the most,” said Lindsay Meredith, a professor emeritus in Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business and an expert in political strategy and marketing, in an interview on Wednesday morning.

Like many other pundits and election-watchers, Meredith’s initial prediction was that a Green surge would damage the NDP – which, he says, he does believe was the case on Vancouver Island.

“If the Greens hadn’t been as successful as they were, we’d probably have an NDP government today,” Meredith said.

But he said the picture becomes far more complicated outside of Vancouver Island and in ridings like New Westminster, traditional NDP strongholds where the Greens managed to raise their popular vote without noticeably affecting New Democrat results.

In New Westminster, Liberal support dropped from 33.37 per cent in 2013 to 21.27 per cent this time out.

“That’s where I say we’re getting some weird new behaviours,” Meredith said. “That’s the part that’s got me shaking my head.”

In part, he said, the Green surge comes from the fact that voters were engaging in what he calls “voter revenge games” – similar in vein to the voting that led to Brexit, to the election of Donald Trump in the U.S. and to the rise (although not the eventual election) of the far-right Marine Le Pen in France.

“It was a dissatisfaction; not voting for who you want, but voting against who you dislike,” he said.

What it boils down to, he said, is that people voted NDP because they were dissatisfied with the Liberals, and they voted Green because they were dissatisfied with the NDP.

But Meredith said many New Democrats in New Westminster – a city with an older demographic – were among the hard-core voters who were unlikely to turn.

“Those older NDP voters tend to be very loyal animals,” he said.

Meredith said the “dissatisfied” voters who made the difference to the Greens – especially in places like New Westminster and Burnaby, with older populations – may in fact have come from the Liberal camp.

From Meredith’s perspective, the Liberals failed on one major front with older voters: health care. He said the Liberals should have paid more attention to the fact that health care was far and away the front-running concern for voters, especially those in that coveted older demographic that’s statistically more likely to vote.

Those previous Liberal voters who were angry about the health-care issue most likely went Green instead, he said.

“I think that was purely a revenge vote,” he said.

Meredith said the NDP likely suffered some backlash on the health-care front, too, faulting Horgan’s campaign for not making it a more central issue.

“It would have been the easiest harpoon to throw,” he said.

But, he said, most of the backlash likely hurt the Liberals and benefited the Greens.

In New Westminster, he said, the Green showing also likely came from its success in engaging new voters.

Campbell herself supports that hypothesis, noting her campaign grew from virtually nothing – there wasn’t a provincial riding association or any base of Green supporters – to a full-fledged campaign with more than 200 volunteers and signs sprouting up all across the city.

“We attracted people from the left and the right and people who have never been involved before,” she said.

During the campaign, Campbell described her campaign as a “big tent” for those from across the political spectrum.

“It’s not a matter of being on the left or on the right anymore,” she said. “It’s about getting behind being issue-based, let’s do what’s right. We don’t need to be so polarized in our politics.”

Campbell said she’s seen interest from a lot of people who are new to politics.

“I think it speaks to that whole desire to get involved with something that is not so established in the traditional political parties,” she said.

Meredith, in the final analysis, sees Green support coming from two camps: the true, die-hard Greens (“those who really are tree-huggers, who recycle religiously, eat kale”) and those who were part of what he sees as that “global revenge vote” – the “I just want to kick over the pot for the sake of kicking it over” voter.

The overall increase in Green popularity in B.C. – from 8.15 per cent of the vote in 2013 to 16.75 per cent this year – was, he says, the outcome of the spoiler effect.

“It turns out the Greens may be the funny magic mushroom that pops up,” he said.

- with files from Theresa McManus

![[UPDATE] New Westminster votes 2017](https://www.vmcdn.ca/f/files/glaciermedia/import/lmp-all/785632-vote.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)