This is part two of a two-part story featuring Waffle House founder Susan Chew, whose life in New Westminster in the 1940s and '50s recall a bustling little city where a young entrepreneur could really make an impression. They also recall a nearly forgotten racist blot on that city’s history. To read part one, click on the link below.

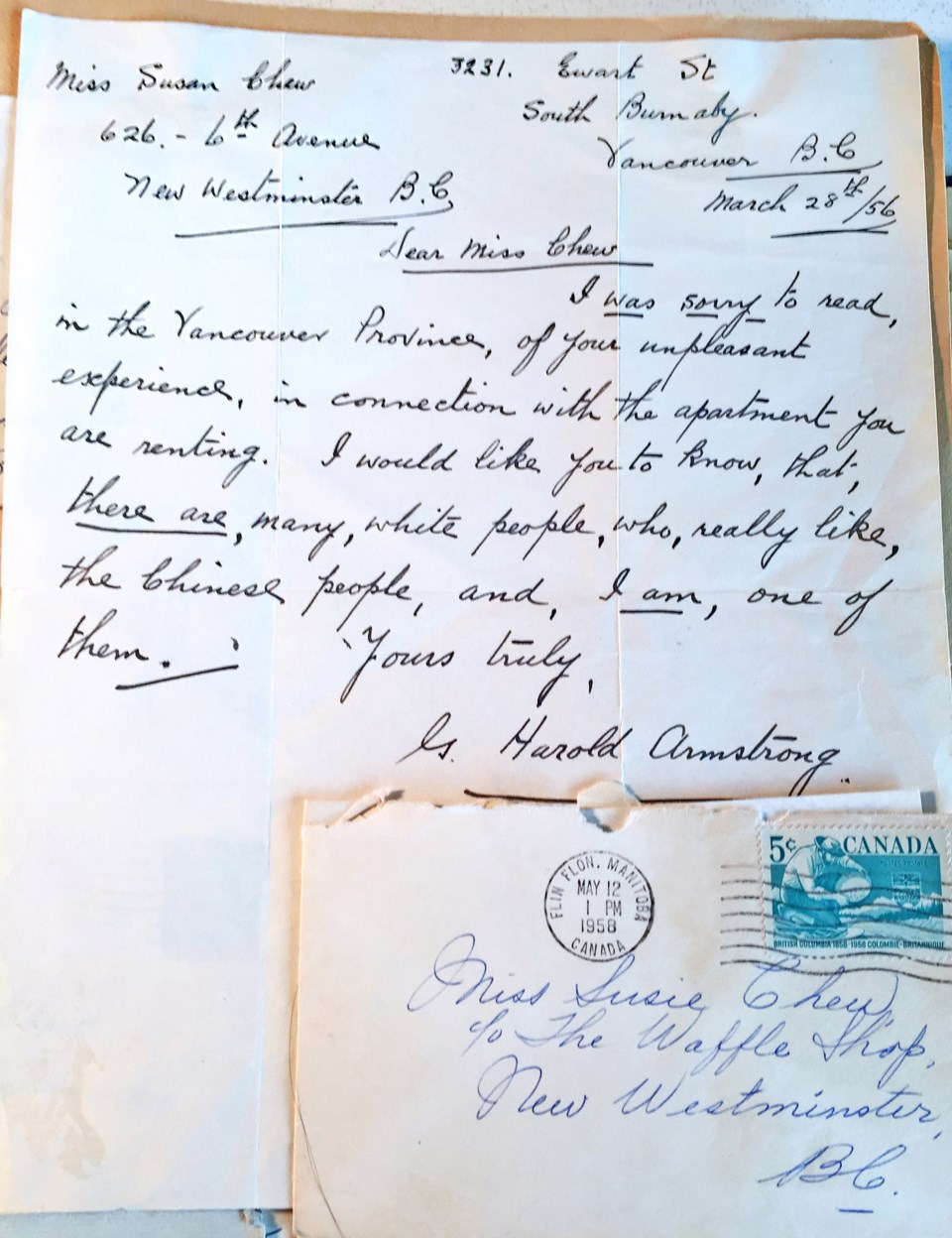

Opening it, I’m taken back to an event in New Westminster’s history that has been all but forgotten.

“Bermuda House Bans Susan Chew” blares the headline on the front page of the March 21, 1956 Columbian above a large photo of a 29-year-old Chew.

An energetic young businesswoman and the proprietor of the popular Waffle House at Sixth and Sixth, Chew and Verla Thompson (née Staples), a friend who waitressed at the café, had paid a deposit on a bachelor suite at the “swanky” new Bermuda House apartments at 1303 Eighth Ave.

Two weeks later, however, manager John McIlroy had changed his tune and quietly told the Victoria-born Chew she couldn’t live there because she was Chinese.

Racial furor

She had driven back from the encounter mortified at the prospect of telling Thompson and their friends in the press – regulars at the Waffle House – why there would be no housewarming party.

“It was devastating,” she says, “I felt ashamed because I was a Cubmaster, I sang in the Baptist choir, I did all kinds of community things, you know, and I felt short-changed.”

When she finally told her press friends, it took them three days to convince her to go public.

When she did, the story spread like wildfire, with CKNW blasting it over the airwaves and the Columbian letting loose with a front-page story and pictures.

“All hob broke loose,” Vancouver Sun columnist Jack Wasserman would write later. “By the late afternoon, a whole city was up in arms …”

Responding to the sudden wave of controversy, McIlroy, the original builder of the apartment block and a part owner, told the press the incident had all been a misunderstanding and it hadn’t been his idea to reject Chew as a tenant.

It had been the work of a U.S. corporation planning to buy the Bermuda.

McIlroy said the prospective owners had seen Chew’s name on the list of tenants, asked about her ethnic origin and then ordered him as manager to reject her.

“No one more than myself regrets the disturbance caused by the incident,” he told the Columbian. “We had no thought of racial discrimination here ...”

Meanwhile, instead of being “snowed under” by people turning against her, as McIlroy had warned Chew they would if she spoke out, the young entrepreneur got an outpouring of support from “a score of indignant friends she never knew she had,” according to the Herald.

Prominent local physician Dr. E.M. Wilder and his wife Susan, a CKNW writer, were scheduled to move into one of the Bermuda’s two penthouse suites, but the couple cancelled their lease in protest, according to the Herald.

“I am dedicated to aid in the alleviation of pain and suffering, not to encourage it with such an act of discrimination,” Dr. Wilder told the paper.

Mayor Fred Jackson also registered his support, calling Chew “a good citizen of good character.”

“It was big news back then,” Chew says, watching me flip through the clippings.

So big was it that Chew would go on to appear on Front Page Challenge, the popular weekly current events show on CBC that once hosted the likes of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Malcolm X and Jesse Owens.

“Triumph of decency”

Within 12 hours of Chew telling her story, McIlroy announced he had cancelled the sale of the Bermuda to the U.S. firm and Chew would be allowed to move into her bachelor suite after all.

That revelation unleashed another round of front-page headlines, editorials, columns and letters to the editor, not just in the local paper, but in the Sun, the Province, the Herald and others.

Many called McIlroy a hero for cancelling the $400,000 deal.

The Province called the move a “triumph of decency.”

The Columbian said New West citizens could thank God the “stain of racial discrimination” had been removed from the city.

Some directed their ire south of the border.

Coun. J.L Sangster told the Herald New Westminster didn’t want “any reputation of Alabama troubles” – referring to riots that had erupted a month earlier at the University of Alabama with the integration of the school’s first black student, Autherine Lucy.

The Province took up the same line.

“This little incident of Miss Chew and her apartment strikes us, somehow, as a much bigger milestone along the road to tolerance and human understanding than all the uproar over Miss Autherine Lucy and the University of Alabama,” read one editorial.

Amidst the patriotic bluster, however, the U.S. corporation that had reportedly sought to impose its American-style racism in the Royal City was never identified.

Some commentators, like Mrs. Tillie Collins, secretary of the Vancouver branch of the League for Democratic Rights, saw the Bermuda House affair as a call to action.

Writing to the Herald, she called on B.C. to join other provinces that had already passed fair accommodation legislation – something the league had unsuccessfully lobbied the province for for two years.

And five years later, when a B.C. Federation of Labour fact-finding committee found the only documented case of housing discrimination in New West had been Chew’s, executive secretary Bill Giesbrecht warned the Columbian any back-slapping on the issue should be cautious.

“Far too many victims of discrimination, through fear of publicity or reprisal, fail to take action and nurse their wounds in private,” he said.

The roommate

While many quoted in the newspapers of the day voiced shocked indignation at the idea of racial discrimination rearing its head in the Royal City, one person close to the story was not surprised.

Thompson wasn’t named in the first stories about the Bermuda House incident and stayed almost entirely in the background for the duration of the uproar.

“She is really not involved, and I don’t wish to cause her any embarrassment,” Chew had told the Columbian about her “Occidental” roommate in 1956.

A small-town girl from the prairies, Thompson had come from Manitoba to live with her two sisters in Surrey.

“We got along great,” Chew says, “and we just thought it would be kind of fun to move in together.”

Once the dust had settled on the Bermuda House affair, they did move into the apartment but only stayed for about a year before Thompson got married and moved to the B.C. Interior and Chew bought a house in New West with her sister

Prior to a 90th birthday party at the Waffle House for Chew in January, the former roommates had lost touch.

Talking to Thompson on the phone – after tracking her down on the internet – it’s easy to see how Chew’s old friend stayed in the background while the media hoopla swirled around Chew.

At one point Thompson tells me I’m asking too many questions.

“I haven’t thought about that place in a long, long, long time,” she says.

There’s just enough time to ask a couple quick questions before she hustles me off the phone.

One of them is about racism.

The discrimination others claimed to find so shocking during the affair didn’t surprise her in 1956.

“No, I’d already been in school, and there was lots of it when we were in school,” she says matter-of-factly.

Not so for Chew, who says she had never encountered racism before.

For her, it took McIlroy telling her to her face that she wasn’t welcome at the Bermuda House to shake her confidence in her place in the community.

“But it was fleeting,” she says, 60 years later. “After that, it was gone. I had to deal with life, you know, carry on.”

Like the appendectomy that released her from a life of farm labour and launched her into a new life as an urban entrepreneur, she says the notoriety that came with the Bermuda House affair eventually opened up new opportunities for her, first in Vancouver and then in Toronto.

And ahead of her still were more adventures: modelling and reporting in China Town, hula dancing in Hawaii, selling real estate in Toronto.

The Royal City, however, would always keep a special place in her heart.

“I was really fond of New Westminster,” she says. “I never forgot New Westminster.”