It started with a pair of shoes. It led to a mission to decolonize the New Westminster Secondary School library.

That journey isn’t as roundabout as it might sound, if you happen to be Sarah Wethered.

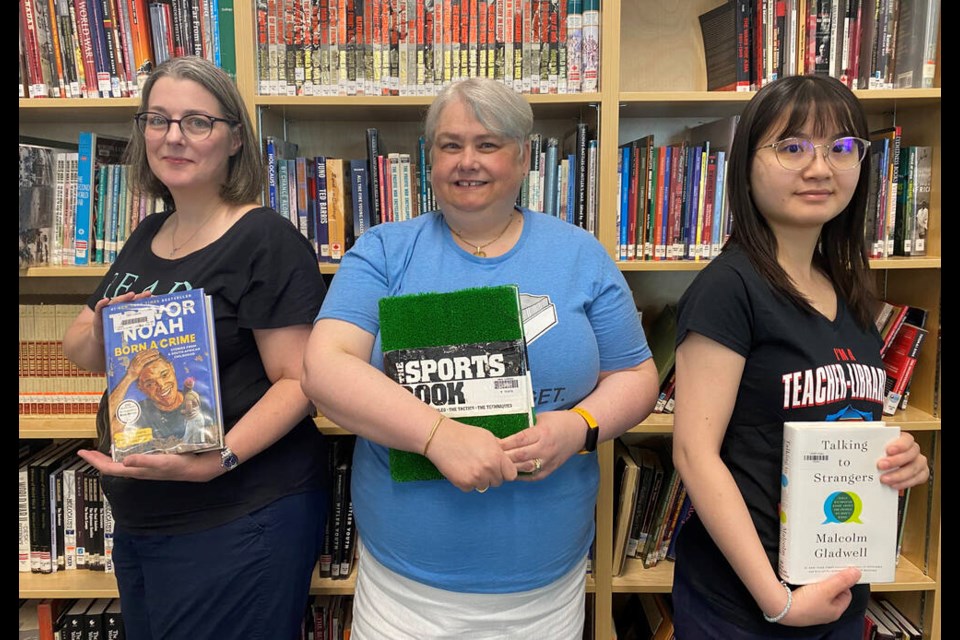

The longtime NWSS teacher-librarian is working with colleagues Jenny Chang and Lisa Seddon on an ambitious project: to transition the library’s non-fiction catalogue away from the Dewey decimal system to a more inclusive method of classification.

The project has its roots in a pair of Fluevog shoes.

Wethered is a shoe aficionado, with a particular fondness for the footwear of Vancouver shoe designer John Fluevog.

Fluevog has a line of shoes known as the Biblio family, which pays tribute to notable librarians past and present. A couple of years ago, a new design was introduced as Melvil, for Melvil Dewey, a founder of the American Library Association.

“That name stuck around for exactly one day,” Wethered said, telling the tale at the New Westminster school board meeting on June 20. “The Fluevog community was outraged and said, ‘You know, maybe you need to look at some background information about Melvil Dewey. He was kind of sketchy, and you may not want to put your name on a shoe with his name.’”

Why? Well, Dewey may have created the famous library classification system that bears his name (he copyrighted it in 1876). But he also got kicked out the very American Library Association he helped to found — for “sexual impropriety,” in 1905.

“He was also racist, homophobic, misogynist, anti-Semitic,” Wethered said.

Even the American Library Association has distanced itself from Dewey, renaming its highest honour from the Melvil Dewey Medal to the ALA Medal of Excellence in 2019.

“So this made me think, so why do we perpetuate the use of the system within our schools?” Wethered said.

Racism, sexism, homophobia 'hard-baked' into Dewey decimal system

As she sees it, there are other compelling reasons to ditch the Dewey decimal classification, too.

Wethered notes that, under the Dewey system, information about equity-seeking groups tends to be classified within a “very narrow and very overcrowded” designation.

“So, for example, women get less than one full number. We are 305.4. We don’t even get the full 305,” she said. “The three hundreds in the Dewey decimal system, which is social science, is kind of like that junk drawer that we have in our kitchen, where you have the old soy sauce packages, that takeout menu, with some rubber bands, a pen that doesn’t work, some batteries that may work, and for some odd reason I always have one plastic fork. And that is the three hundreds.”

Seddon noted all the issues with Dewey himself — racism, sexism, homophobia — are “hard-baked” into the classification system.

“It shoves women, BIPOC people, 2SLGBTQ people, into very tiny categories, and because of that, it takes them out of the context of everything else around them, and it doesn’t always make sense,” Seddon said.

Then there’s the Eurocentric nature of the system, which Wethered noted forces information about Indigenous peoples into a small historical section and doesn’t acknowledge any of its complexities or current realities.

Likewise with languages and religions. Seddon pointed out that if you’re producing a dictionary or thesaurus in a Western European language, you get a full number all to yourself; every other language is crammed into one section. Similarly, Christianity dominates the classification categories in religion.

“If you’re Jewish or Sikh or Hindu or Muslim or anything else, you’re crammed off into this one number on the side,” Seddon explained.

Who was Brian Deer? Mohawk librarian created Indigenous-based classification system

The question then became: If not the Dewey decimal system, then what?

That’s where the Brian Deer classification system comes in.

Seddon noted Deer isn’t a widely known or widely taught figure in North American library schools. But once she and Wethered started investigating alternatives to Dewey, they found Deer: a Mohawk librarian who developed a system to classify books based around Indigenous content and Indigenous ways of knowing and disseminating information, starting in the 1970s.

“As we’re including more and more authentic Indigenous texts in our libraries, we need to find new ways to classify them so that students can find them,” Seddon said.

With the Deer system, they’re able to be flexible with their collections and prioritize Indigenous content.

The Deer system allows the library to develop its own flexible approach to cataloguing based on letters, rather than numbers, starting with A for reference materials and working through broad and adaptable classifications based on local needs.

For instance, their goal is that the first item in the languages section will be an Indigenous language dictionary.

“Indigenous people were here first. This is their land that we’re on. Their language takes precedence over ours,” explained Seddon.

The New West librarians note the system is already in use in a few places: at the Xwi7xwa Library at UBC and the Indigenous Curriculum Resource Centre at SFU. It’s also being used by some schools in Surrey, though only for their Indigenous content thus far.

They aim to have New Westminster become the first school district where a library’s entire non-fiction collection is catalogued under the Deer system.

It’s no small undertaking.

This spring has seen them firming up subject headings to be used in the new catalogue and creating a manual for implementation. They’ll work throughout the next school year, from September 2023 to June 2024, to re-catalogue their non-fiction collections, with an anticipated finish date of June 30, 2024.

As for whether the change will confuse the students?

Wethered laughs and says the Dewey decimal numbers are just “witchcraft” to most students anyway.

“Numbers or letters, it doesn’t really matter,” she said.

Seddon agrees.

“Really basic, base level? It’s just an address.”

On a broader philosophical level, though, it’s much more.

As Seddon sums it up in an idea from the Simon Fraser University collection: “Information organization influences the way we view reality.”

Follow Julie MacLellan on Twitter @juliemaclellan.

Email Julie, [email protected]