The overdose crisis in B.C. is “craziness that shouldn’t be happening,” according to a New Westminster-based advocate.

That’s part of the message from Lynda Fletcher-Gordon, program coordinator with the Lower Mainland Purpose Society, on International Overdose Awareness Day. What’s more, she said we know the solution – it simply hasn’t had the necessary political backing so far.

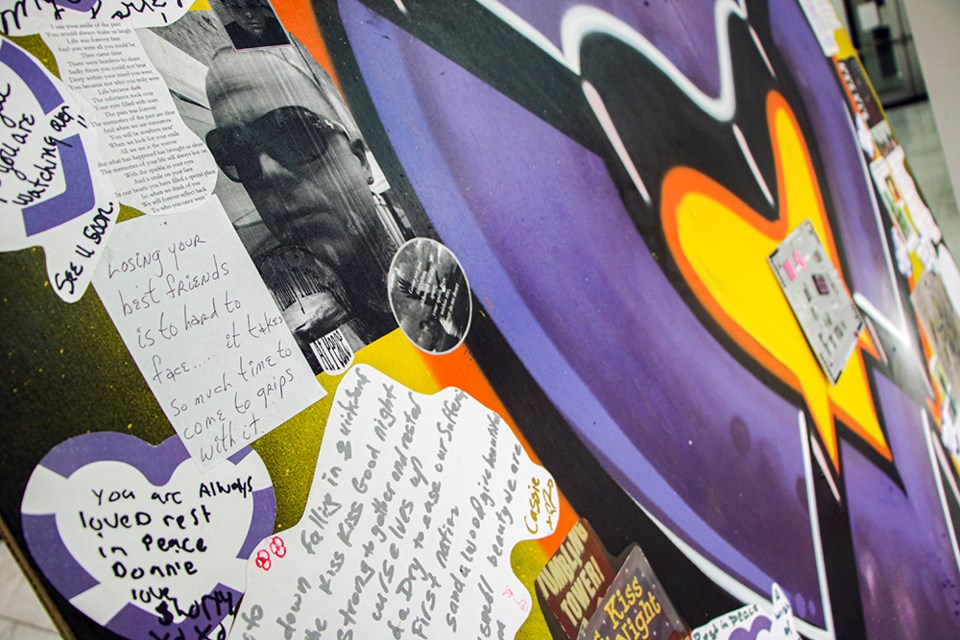

Fletcher-Gordon made the comments as the New Westminster Community Action Team on the overdose crisis set up its memorial to victims at the Anvil Centre. The memorial is expected to stay up all week.

In B.C. and throughout Canada, some aspects of harm reduction have seen significant boosts, including the proliferation of safe consumption sites and take-home naloxone kits. But there are two significant pieces experts in the field say are still missing: a safe supply and decriminalizing drug users.

“The government has placed a lot of faith in naloxone, … but naloxone is no longer enough,” Fletcher-Gordon said. “To place the burden on frontline workers to be there delivering naloxone in order to reduce the number of deaths is just unrealistic pressure.”

A safe supply, on the other hand, involves doctors or nurse practitioners prescribing pharmaceutical heroin or hydromorphone to drug users to divert them from the increasingly contaminated drug supply on the streets. In recent years, fentanyl and related synthetic opioids have infiltrated the market because their high potency makes importing the substance easier. But inconsistent practices can lead to higher doses of fentanyl in some batches than in others.

A safe supply is permitted for a handful of drug users, but advocates say the initiative doesn’t go nearly far enough.

“I’ve heard lots of reasons why a safer supply can’t be provided to folks, but I think none of them are valid,” she said.

“We really, really need to look this square in the eye for what it is, which is a contaminated drug supply. Nothing more, nothing less.”

A safe supply is a mix of federal and provincial jurisdictions – the federal government needs to allow exemptions from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, while the province regulates aspects of how it is delivered.

Decriminalization, too, can be enacted, to varying degrees, by the federal and provincial governments. While the CDSA is federal legislation that would need to be repealed, the province has levers at its disposal to enact de facto decriminalization. Such was a 2018 proposal from Dr. Bonnie Henry, B.C.’s provincial health officer and top public health doctor, who has gained a cult following during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fletcher-Gordon drew parallels between the pandemic and the overdose crisis, noting the disparity in responses from various governments in terms of resources allocated to fight the dual crises, broadly favouring the pandemic. Similarly, while the B.C. NDP has paid significant deference to Henry during the pandemic, the government quickly dismissed her proposal for decriminalizing drug users.

Fletcher-Gordon said she felt the B.C. government has little choice now but to heed Henry’s advice, partly because of her surge in popularity and partly because of a recent surge in overdose deaths. While overdoses had been slowly declining in the year prior, those figures surged to record levels this summer, with two months straight of 175 overdose deaths.

This is largely attributed to disruptions in the supply chain, leading to even greater contamination in the supply.

But New Westminster-Burnaby MP Peter Julian, with the federal NDP, deflected blame to the federal Liberal government, which has refused to consider decriminalizing simple possession of drugs.

“I think that the B.C. government has done as effective a job as they can, given that they’re in an area of provincial jurisdiction and given that the lion’s share of the tax dollar goes to the federal government,” Julian said.

“The federal government has been very negligent as this crisis has developed.”